Chapter 3

Recycling helps manufacturers avoid environmental responsibility.

Before recycling was popular, a refillable-container system prevented trash.

Today, consumers are accustomed to throwing away containers and packaging after use. Before the 1950s, products like beer, soft drinks, milk, and yogurt came in refillable “two-way” glass containers (Jaeger, Elmore). Two-way containers were durable, cleanable, and easily refilled with new product multiple times.

During this era, consumers paid a refundable cash deposit, sometimes as much as 40 percent of the purchase price, when they bought products in returnable containers (Elmore). After use, consumers returned the empty containers to the manufacturer, and received their deposit back. Containers like glass soft drink bottles typically made 25-50 round trips between bottlers and consumers (Elmore).

The two-way container system used in the first-half of the 20th century eliminated waste because manufacturers put a price on trash. Empty containers were valuable to consumers and companies alike. Consumers were incentivized to return used bottles instead of throwing them away, and manufacturers saved money on the costs associated with purchasing new containers.

In the 1950s, beverage companies dismantled the two-way container system to boost profits.

After World War II, the beverage industry changed the way people consumed its products. In the early 1950s, many beer and soft drink companies stopped bottling beverages in refillable containers in favor of disposable one-way containers (Elmore, Jaeger). Using disposable containers helped companies avoid the transportation and cleaning costs for refillable bottles on the return trip. (Elmore). Beverage companies dismantled the highly successful two-way container system in order to streamline their operations and make more money (Elmore).

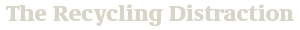

And with disposability, came litter.

Unsurprisingly, switching from the two-way container system to a one-way system with disposable containers came with some environmental drawbacks (Jaeger, Elmore). As more and more disposable cans and bottles were sold, cities and towns were naturally forced to collect, transport, and dispose more container waste.

When companies switched to disposable containers, they also eliminated the need for consumers to pony up cash deposits when they bought products in returnable containers. Deposits ensured empty containers had economic value, but without them, used bottles were practically worthless (Elmore).

In addition to needing to deal with more waste after the switch to disposable containers, America was also forced to confront a new form of pollution tainting the landscape in the early ‘50s: litter (Elmore, Jaeger). Litter quickly became a significant concern for environmentally minded Americans, many of whom blamed manufacturers for creating the problem.

In the mid-1950s, the fight over litter entered political arenas.

The public’s concern over the litter problem became political in 1953 when lawmakers in Maryland and Vermont attempted to restrict the use of single-use disposable beverage containers (Elmore). Maryland legislators proposed a bill requiring refundable deposits on all disposable beer bottles, but it did not have enough support to become law (Elmore). Vermont was marginally more successful. In February 1953, Vermont passed a law banning single-use disposable beer bottles in the state, which one estimate showed reduced litter by up to 90% (Jaeger). Unfortunately, Vermont’s law was struck down after only four years. In 1957, Vermont’s newly created Litter Commission repealed the law after meeting with consultants from the beverage and packaging industries. These consultants urged the Litter Commission to dismantle the law, saying it could set a dangerous precedent for manufacturers in the future (Jaeger).

Between and the late 1970s, lawmakers across the country proposed thousands of laws aimed at restricting the use of non-returnable beverage containers. Very few became law (Elmore). Today, only ten states have container deposit laws (NCSL).

The beverage and packaging industries developed a strategy to blame people for litter.

Around the time Maryland and Vermont were working on laws to restrict the use of single-use disposable products, the beverage and packaging industries developed a joint strategy to protect themselves from the threat of future legislation (Elmore). Companies like Coca-Cola and Pepsi knew that if Americans continued blaming manufacturers for the litter problem, it was likely that more states would pursue laws restricting disposable containers and packaging (Elmore). Container deposit laws posed a serious threat to the industry’s profitability and their public image (Elmore, Jaeger).

Their strategy was simple: avoid regulations on disposable packaging by blaming individual consumers, not manufacturers, as the source of the widespread litter problem (Jaeger, Elmore). This strategy is known as individualism, or the individualization of environmental responsibility (Maniates).

To enact their strategy, companies needed to change the way Americans talked about waste, pollution, and environmental responsibility. So in 1953, companies from the beverage, packaging, and canning industries set aside their competitive differences to establish a third-party organization to carry their message to lawmakers and the general public: Keep America Beautiful (KAB).

The beverage and packaging industries established Keep America Beautiful to distract Americans with busywork.

Keep America beautiful was established as an anti-litter organization. From the outside, KAB seemed to be a grassroots operation working to address litter-related problems for the public good. But in reality, KAB’s mission was to advance the corporate strategy of individualization – blaming people for systemic problems like litter – through advertising, education campaigns, and lobbying activities (Jaeger, Elmore, Dunaway).

“KAB’s central objective was to deflect accusations that corporations were to blame for the country’s growing litter problem… Through targeted education programs, national publicity campaigns, and local clean-up drives, KAB worked to persuade consumers that private citizens, not corporate citizens, should be responsible for waste disposal.” (Elmore, p. 243)

Today, KAB has more than 700 affiliates across the country (KAB). The organization has embedded itself within all levels of civil society to keep Americans busy cleaning up litter, planting trees, and recycling (Jaeger, KAB). These activities may provide modest environmental benefits, but they don’t address litter problems at the source: companies that manufacture billions of non-biodegradable disposable products every year.

KAB keeps Americans distracted with busywork so they don’t challenge manufacturers on environmental issues through political channels.

KAB sold individualism to Americans through national advertising campaigns.

A full-page “Susan Spotless” ad by Keep America Beautiful, from Time Magazine, April 2, 1965.

During the mid-1960s, Keep America Beautiful ran emotionally charged ads with the character Susan Spotless. In the ads, Susan, a supposed emblem of purity, shamed her parents with a pointed finger as a reminder to avoid littering.

Keep America Beautiful. Photograph by the author of the item in his personal collection.

The beverage industry used KAB to change the way Americans think and talk about environmental responsibility – from blaming manufacturers for waste and pollution, to blaming individual people. KAB accomplished this goal through advertising and widespread public service announcement (PSA) campaigns (Dunaway).

In the 1950s and ‘60s, KAB created ad campaigns such as “Susan Spotless” and “Pigs”, to stoke a sense of moral duty in Americans to eschew littering. However, KAB’s most famous – or rather infamous – effort was the now iconic “Crying Indian” campaign that debuted in 1971, exactly one year after the first Earth Day (Dunaway, Jaeger, Elmore).

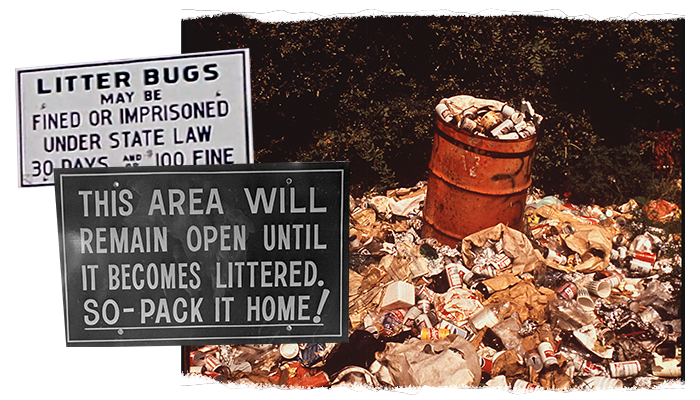

The Crying Indian ad campaign featured a television commercial starring actor Iron Eyes Cody dressed in a historic, Native-American-looking outfit, complete with long, braided hair and a feather over one ear. In the commercial, Cody paddles a canoe down a bucolic stream into a modern-day setting, only to have a bag of fast-food trash thrown at him by passing motorists. The motorist’s careless act forces a single tear from the stoic character, communicating deep feelings of sadness and regret about the state of the world. A narrator drives the point home by closing the ad with the guilt-ridden tagline, “People start pollution. People can stop it.”

Keep America Beautiful used the Crying Indian ad campaign to stoke a national sense of guilt about litter, waste, and pollution (Dunaway). The campaign set the stage for recycling to enter the mainstream by convincing people that only individual actions, not regulations or systemic change, can protect the environment from the excesses of economic activity (Jaeger, Elmore).

01 | Still images from the 1971 “Help Fight Pollution” (Crying Indian) television commercial

The iconic “Crying Indian” commercial starred Italian-American actor “Iron Eyes” Cody and ended with the closing line “People start pollution. People can stop it.”.

The commercial launched a massive ad campaign that convinced Americans that individual people – not companies – created pollution, and therefore, people were responsible for cleaning it up.

Keep America Beautiful and the Ad Council. Stills captured from a digital video file courtesy of the Ad Council Archives, University of Illinois.

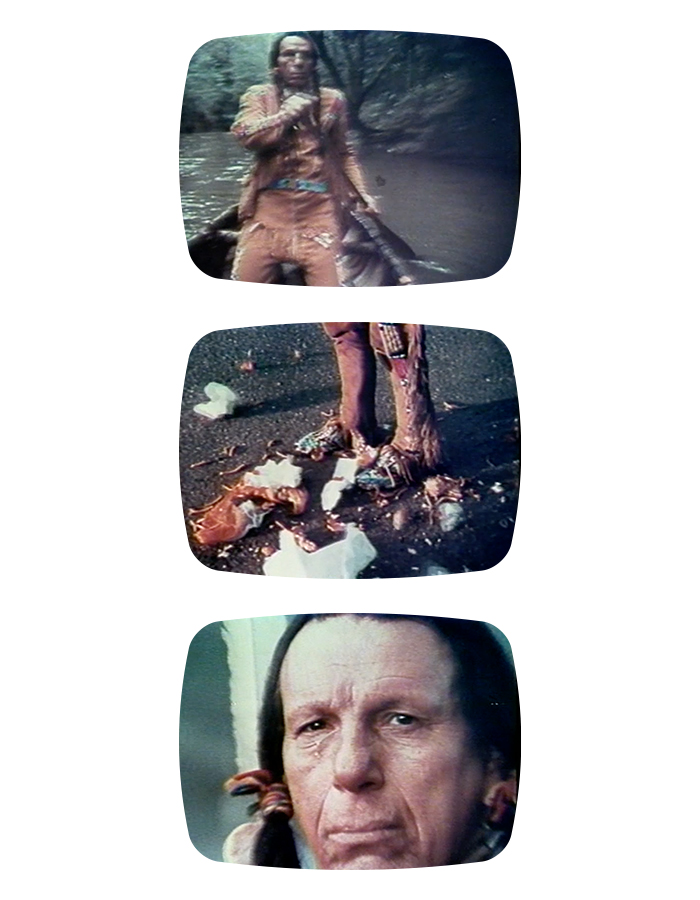

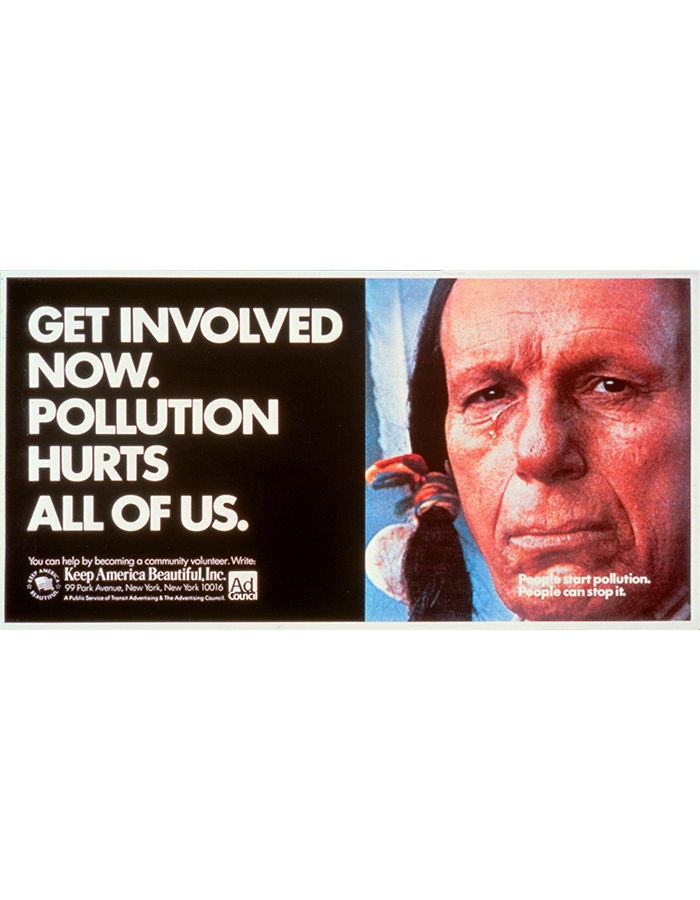

02 | “Help Fight Pollution” print advertisement, 1971

During the 1970s, the television commercial was adapted for distribution across multiple forms of media. Here, a print ad encouraged people to request Keep America Beautiful’s booklet, “71 Things You Can Do To Stop Pollution.”, for ideas on activities to benefit the environment.

Keep America Beautiful and the Ad Council. Courtesy of the Ad Council Archives, University of Illinois.

03 | “Help Fight Pollution” bilboard advertisement, 1971

The iconic photo of the teardrop on Cody’s face is used throughout the campaign. Here, in this bilboard advertisement, the image is cropped tightly to emphasize the tear and the sorrowful expression on Cody’s face. These emotional elements were designed to underscore the written message and motivate viewers into action.

Keep America Beautiful and the Ad Council. Courtesy of the Ad Council Archives, University of Illinois.

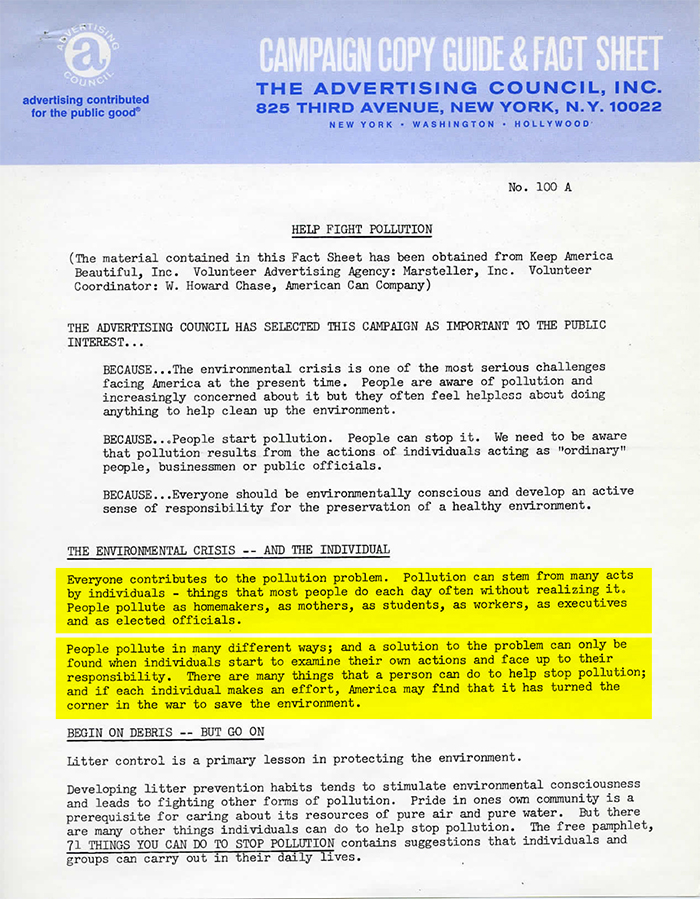

04 | “Help Fight Pollution” copy guide and fact sheet (page 1), 1972

In 1972, the Ad Council sent this “Campaign Copy Guide & Fact Sheet” to radio broadcasters along with audio recordings and scripts for 10-, 30-, and 60-second public service announcements.

The guide informed broadcasters about individualized environmentalism and how to communicate campaign messages to audiences. It is evidence of Keep America Beautiful’s strategic efforts to blame people for pollution while ignoring the role of Industry in creating environmental problems.

Note that an executive from the American Can Company is listed as a “Volunteer Coordinator” for the campaign.

Keep America Beautiful and the Ad Council. Courtesy of the Ad Council Archives, University of Illinois. Highlighting added by the author for emphasis.

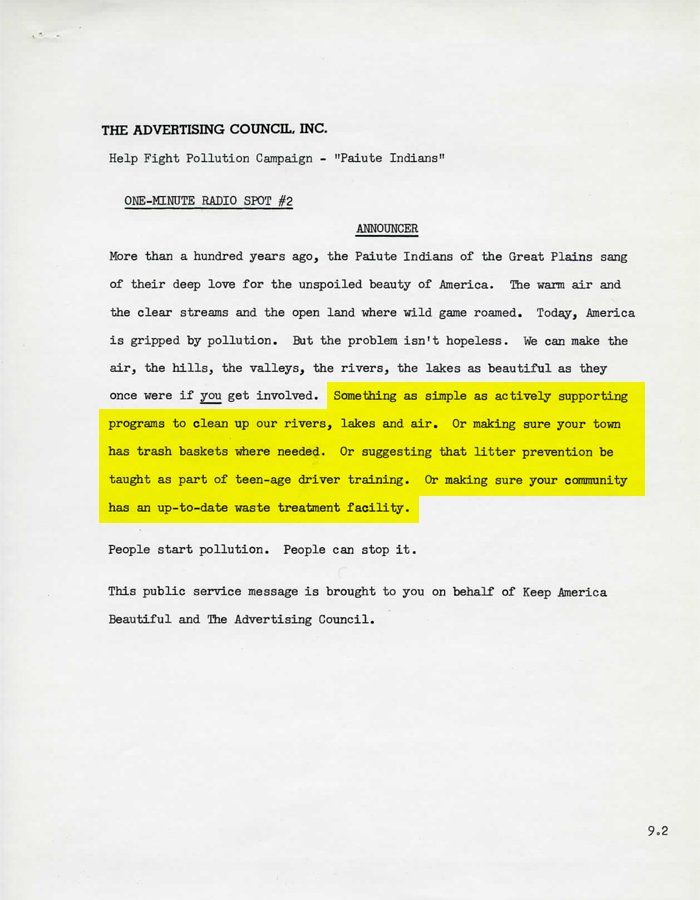

05 | “Help Fight Pollution” campaign radio script, 1972

The Ad Council provided this script for a 60-second public service announcement to radio broadcasters in 1972. The radio ads echoed the sentiments from the television commercial, relying on guilt as a motivational lever. The first paragraph concludes with suggestions for how people could prevent litter and clean up pollution – none of which involve scrutinizing companies for their roles as polluters.

Keep America Beautiful and the Ad Council. Courtesy of the Ad Council Archives, University of Illinois. Highlighting added by the author for emphasis.

Individualism paved the way for ubiquitous recycling.

In the mid- to late-1970s, KAB followed up their advertising efforts with educational campaigns designed to spread the word about volunteer litter cleanups to thousands of schools, non-proft organizations, and local governments (Jaeger). KAB also developed and promoted their “Clean Community System (CCS),” a program to help local government organizations track and monitor progress on cleaning up litter in their communities (Jaeger).

Despite these efforts, cities across the country struggled to keep up with the increasing amounts of trash being thrown away each year (Jaeger). In the early 1980s, the country experienced a solid waste crisis. Americans feared there wasn’t enough space in the nation’s landfills to hold all the stuff they were throwing away (Jaeger).

In 1982, KAB ramped up their efforts to promote recycling. The organization worked in tandem with the beverage and packaging industries to convince lawmakers, environmental organizations, and the general public to adopt recycling instead of container deposit laws to prevent litter. Recycling was positioned as a “win-win-win” solution to problems with container waste (Jaeger, Elmore).

Recycling boomed in the United States during the 1980s and ‘90s. In 1989, there were roughly 600 curbside recycling programs across the country. Three short years later in 1992, there were more than 4,000 (Elmore).

Individualism is a distraction.

Today, in America, recycling is institutionalized individualism. Recycling and other activities that happen at the individual level, like litter cleanups, are environmental busy work (MacBride). At best, they have marginal reductions on waste and pollution in the short term, but long term, they distract people from scrutinizing the underlying systems that produce so much waste in the first place (Maniates, Maniates).

Since the 1950s, the beverage and packaging industries have made significant efforts, many through Keep America Beautiful, to convince Americans that small activities like recycling, can add up to big change on environmental problems. History shows us that this is part of a a strategy companies use to avoid sensible regulation of disposable products.

Recycling keeps you acting in the realm of the individual – that is to say, it keeps you distracted with individualized activity so you don’t consider using political channels to address environmental problems. When it comes to limiting waste and pollution caused by disposable products, companies would rather you recycle instead of vote.

Chapter 2: The environmental benefits of recycling are misunderstood and overrated.

Chapter 4: Recycling won’t prevent America from drowning in plastic waste.