Chapter 2

The environmental benefits of recycling are misunderstood and overrated.

To achieve the environmental benefits, manufacturers need to replace virgin materials with recycled materials.

Recycling has the potential to deliver the environmental benefits listed above, but unless products are made with recycled materials, the benefits are either overrated or misunderstood.

The next time you buy something, look at the label. Does it say the package or container is made with 100 percent post-consumer recycled materials? No? Then virgin raw materials and lots of energy were needed to manufacture it. Making products from virgin materials takes a huge toll on the environment and the people who live where natural resources are mined or otherwise extracted – concerns recycling was supposed to help society avoid.

Another downside to using virgin raw materials is that it introduces more overall materials into the economy that will eventually need to be disposed. Unfortunately, in most cases, recycling only delays inevitable disposal (Zink and Geyer).

The only way for recycling to deliver its purported environmental benefits is to displace virgin raw materials with recycled materials during the manufacturing process (Zink and Geyer).

America continues to generate more trash decade after decade.

Recycling was supposed to be a way for Americans to reduce waste. The idea being that if consumers recycle containers and packaging after use, valuable materials won’t end up in a landfill, or worse, become litter.

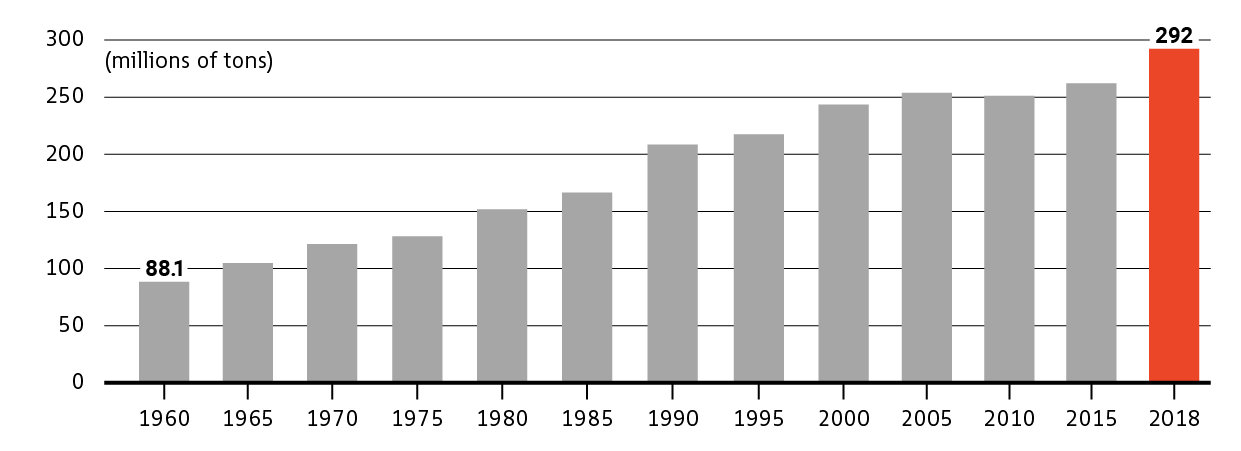

Check out the EPA’s data on municipal solid waste – the official term for “trash” – in the U.S., and you’ll see that America keeps throwing away more stuff year after year.

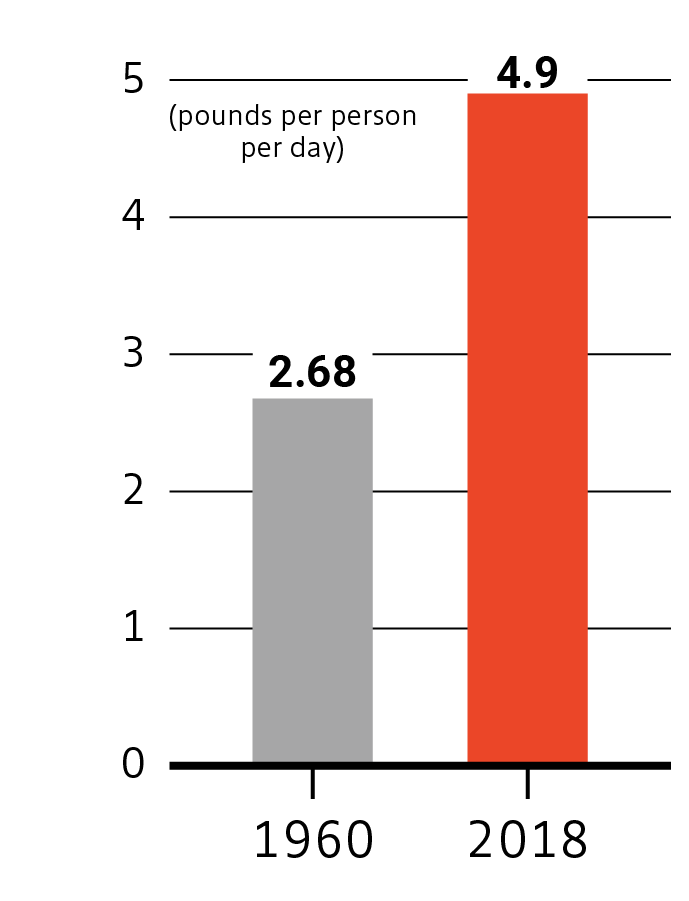

In 1960, Americans generated more than 88 million tons of municipal solid waste at a rate of 2.68 pounds per person, per day. Six decades later, America produced three times as much total waste. In 2018, the most recent year the EPA published data on the subject, Americans threw away more than 292 million tons of trash, at 4.9 pounds per person, per day (EPA).

The dramatic increase in the rate people throw away trash, from 2.9 pounds per person per day in 1960 to 4.9 pounds per person per day in 2018 is a major red flag that recycling isn’t reducing the total amount of stuff America throws away. The American recycling system simply wasn’t designed to keep pace with an economy built to continually generate more and more waste.

Total US municipal solid waste generation, 1960-2018.

Adapted from US EPA National Overview: Facts and Figures on Materials, Wastes and Recycling.

Per-capita trash generation.

Infinite, closed-loop recycling rarely occurs.

The recycling symbol is one of the most recognizable marks in the world. It’s emblazoned on all sorts of consumer products and packaging, including bottles, cans, jars, boxes, bags, and much more. You have probably already encountered the symbol multiple times today.

The symbol is ubiquitous and a powerful daily reminder to participate in recycling. Its triangular, chasing-arrows design suggests that recycling keeps materials in use forever, like some form of industrial reincarnation (Dunaway).

There is potential for some materials to be infinitely recycled. But in reality, recycling is often a slow, downward spiral to the landfill, incinerator, or worse, pollution. Materials often loose value during the recycling process – a phenomenon called downcycling – and will be made into products that won’t be eligible for recycling again (McDonough and Braungart).

In America, plastics are usually downcycled. PET, the plastic used to make soda bottles, and HDPE used to make milk jugs, are the two most-recycled plastics in the U.S. (Heller, Di). More than 70 percent of PET will be downcycled into polyester fiber to make clothing and other textiles (Li Shen and Patel). HDPE is usually downcycled to make storage crates and other durable containers (Andrady). In the U.S., clothing, textiles, and durable products are rarely accepted in curbside recycling systems (ASTRX, Mouw). And forget about plastics #3–7 being beneficially recycled – these “junk plastics” are almost always landfilled, incinerated, or exported to countries in Asia (Di, Brooks, Heller).

Metals, paper, and glass have a better chance of being recycled multiple times, but not by much. Paper is good for 5-7 recycles before its fibers are too small and weak to be recycled again. Metals loose value when alloys are mixed, and unless glass is sorted by color, it will usually be downcycled into products like fiberglass or artificial sand (McDonough and Braungart, MacBride).

More than 70 percent of recycled PET bottles will be turned into polyester fiber, not more bottles.

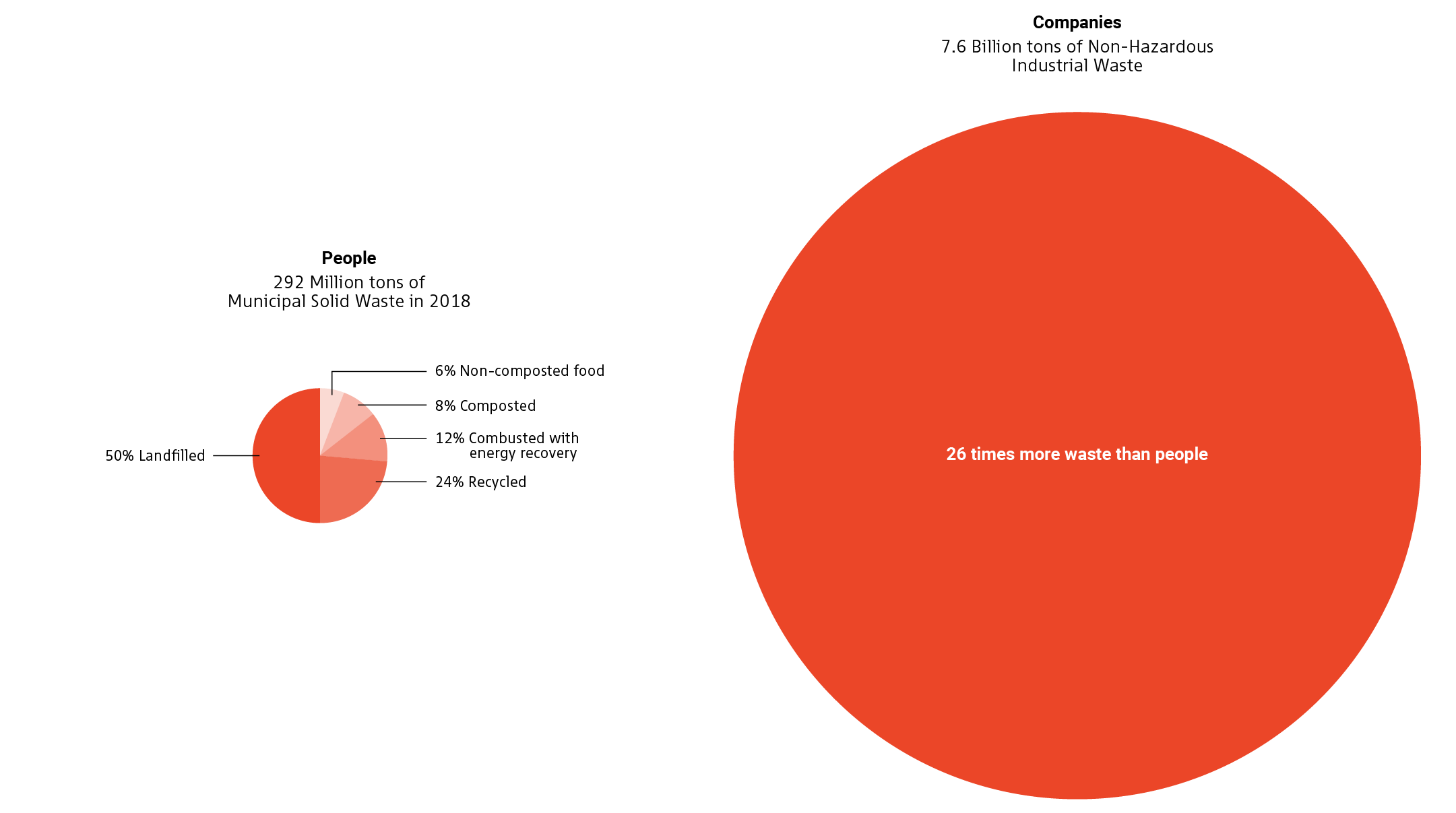

Companies generate far more waste than people.

Another problem with recycling is that it gets more attention than it deserves. Recycling keeps people, organizations, and governments focused on managing and reducing municipal solid waste – trash that is visible to the public. However, the 292 million tons of trash America creates every year is a drop in the bucket compared to the vast amounts of unseen manufacturing waste that companies generate upstream in the economy.

In 2016, the EPA published the Guide for Industrial Waste Management, a 478-page document designed to help factory managers, regulators, and the general public learn best practices for properly disposing non-hazardous industrial waste (EPA). The guide states that manufacturers generate 7.6 billion tons of industrial waste[1] every year. Meaning that during the manufacturing process, companies generate about 26 times more waste than consumers!

Annual waste generated in the United States–people vs. companies.

Sources: US EPA National Overview: Facts and Figures on Materials, Wastes and Recycling; Recycling Reconsidered by Samantha MacBride; US EPA Guide for Industrial Waste Management.

Without comprehensive data, companies are shielded from public scrutiny about industrial waste.

The EPA started collecting data about municipal solid waste in 1960, so we know a lot about the stuff people throw away and how trash is managed. Today, most states conduct comprehensive studies to learn what’s in their trash and where the materials go after being collected. The EPA compiles and shares this data with the public so people and governments can make informed decisions about municipal-waste-management issues (EPA).

Unfortunately, when it comes to issues related to industrial waste, people and lawmakers are relatively uninformed. For decades, companies and industry groups have fought to make sure reporting data about industrial waste remains voluntary (MacBride). As a result, the American public knows very little about the characteristics of industrial waste and how companies dispose of it (MacBride).

Without robust and accurate data about industrial waste, it’s very difficult for people and lawmakers to hold manufacturers accountable for their fair share of environmental problems.

Recycling’s benefits are mostly economic.

Recycling hasn’t done much to reduce waste in America, but it does provide some economic benefits. The EPA’s 2020 Recycling Economic Information (REI) report shows that every year, the recycling economy supports about 681,000 jobs, $37.8 billion in wages, and $5.5 billion in tax revenues (EPA).

One important caveat of the REI, is that the report includes economic data from industries indirectly related to recycling, such as the power plants that supply energy to run recycling facilities, and information about materials collected for recycling outside municipal systems, such as construction waste and rubber from used tires.

Recycling has many negative impacts on workers and neighborhoods.

Recycling’s economic benefits come at a huge cost to workers and people who live near recycling facilities.

The work of collecting, transporting, and sorting recyclables is incredibly hazardous. In 2020, the Bureau of Labor Statistics found that trash and recycling collection is the fifth most dangerous civilian job in the country (BLS). And work at the sorting facilities isn’t much better. High-tech equipment enables much of the sorting process to be automated, but a surprising amount of human labor is still needed to remove contaminants from the waste stream. Sorters work all day next to heavy, fast-moving equipment, and are exposed to hazardous chemicals, persistent dust, and harmful objects on the sorting line (NIOSH).

Unfortunately, in urban America, MRFs and other waste-processing facilities are typically located in industrial zones next to low-income neighborhoods (MacBride). Residents in these areas are disproportionately impacted by negative side effects from MRFs, like excess noise, pollution, and the continual flow of trash trucks driving through the neighborhood.

Recycling distracts people from confronting an economy designed to create waste.

Take

Extract finite natural resources

Make

Manufacture single-use disposable goods

Waste

Dispose containers and packaging

Take

Extract finite natural resources

Make

Manufacture single-use disposable goods

Waste

Dispose containers and packaging

The American consumer-goods economy is a linear, take-make-waste system. Companies extract raw materials from the earth to make goods for consumers to buy. The goods are designed to be disposable so companies can sell goods faster. Waste and pollution are simply inevitable results of a linear economy that defines progress as producing more goods year after year.

Problems created by this economy, such as excess waste and litter, are often framed in terms of the individual consumer. Trash is called “consumer waste” and the word “litter” is used to highlight pollution generated by individual people. And “consumerism” carries a negative connotation, suggesting that consumers’ obsessive purchasing habits are solely to blame for widespread environmental problems. But focusing conversations about environmental problems in consumer-centric terms leaves the role of producers (manufacturers) out of the conversation, and therefore out of reach of criticism.

Where is the widespread criticism of “productionism”?

Since the 1960s, recycling has been promoted as the antidote to the excesses of the linear economy. People learn through educational programming and government-sponsored PSA campaigns, that it is their duty to reduce waste and prevent pollution by recycling (Jaeger, Dunaway). Recycling is promoted as the way people can “close the loop” to keep valuable materials in use for perpetuity, offering consumers a sense of redemption for buying disposable products (Dunaway).

Unfortunately, recycling distracts consumers from confronting the system that creates the conditions for so much waste to be created in the first place. In the next chapter, we’ll see how the beverage industry, not environmental groups or a government initiative, helped make recycling popular in America.

Chapter 1: Recycling in America.

Chapter 3: Recycling helps manufacturers avoid environmental responsibility.