Chapter 4

Recycling won’t stop America from drowning in plastic waste.

Most plastics have never been recycled.

Aside from steel and concrete used in the construction industry, plastics are one of the most abundant human-made materials on earth (Geyer, et al.). Plastics were first used to manufacture goods in the 1920s, but the material wasn’t as ubiquitous then as it is today. World War II marked a turning point for plastics as global plastics production ramped up significantly in the 1950s. Since then, more than nine billion tons[1] of plastics have been produced around the world (Geyer, et al.).

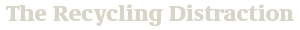

As of 2015, fewer than 10 percent of all plastics ever made have been recycled, and only a tiny fraction of those have been recycled more than once (Geyer, et al.). Sadly, most plastic waste is landfilled, incinerated, or ends up as pollution (Geyer, et al.).

In the United States, more than three-quarters of plastic waste is buried in landfills, not recycled (Heller, Di).

Global Recycling Rate for All Plastics Ever Made (1950-2015)

Source: Geyer, Jambeck, and Law, “Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made.” Science Advances, 2017.

With more factories being built, the plastics problem will likely get worse.

Since the 1960s, companies have produced more and more disposable plastics. As a result, the proportion of plastics in America’s trash continues to grow. In 1960, less than 1 percent of America’s trash was plastic. Three decades later in 1990, it was 8.2 percent. And in 2018, plastics accounted for 12.2 percent of materials in America’s garbage.

Unfortunately, recycling hasn’t kept pace with the rate America generates plastic trash. Since the 1990s, the average recycling rate for plastics in the U.S. has been 6-9 percent (EPA, Heller, Di).

The American recycling system simply wasn’t designed to process the amount of plastic waste America generates. One reason for this is that 60 percent of America’s plastic waste isn’t even eligible for municipal recycling (Heller, Di). The U.S. recycling system was designed to collect only discarded containers and packaging – bottles, cans, and the like. Other types of waste, for example, from automotive products or construction debris, are not accepted in U.S. curbside recycling programs.

America’s abysmally low recycling rate for plastics is troubling when you consider that since 2010, petrochemical companies have been investing billions to build factories to produce millions of tons of new plastics (ACC, Yale360).

If the current U.S. recycling system is inadequate to capture existing amounts of plastic waste, how could it possibly stop America from drowning in the flood plastics from hundreds of new factories?

The link between the U.S. recycling system and ocean plastic pollution.

For decades, many U.S. recycling programs have collected low-value plastics – #3 Polyvinyl Chloride (PVC), #4 Low-Density Polyethylene (LDPE), #5 Polypropylene (PP), #6 Polystyrene (PS), and the #7 “Other” category – but haven’t actually recycled them. These plastics are used to used to make a wide variety of commonly available products like yogurt cups, coffee cup lids, straws, take-out containers, and toys.

Instead of being recycled, plastics #3-#7 are usually landfilled or incinerated (Brooks, Di, EPA). Sometimes, American waste-management programs become so overwhelmed with plastic waste they ship the materials overseas (Brooks, et al.).

From 1992 to 2016, the U.S. exported 29 million tons of plastic waste to China and Hong Kong (Brooks, et al.). After China tightened restrictions on foreign waste in 2018, the U.S. enlisted other countries to accept its junk plastic, like Thailand and Malaysia (Brooks, et al., Wang, et al.).

Unfortunately, many countries that import American plastic waste often have underdeveloped waste-management systems themselves (by U.S. standards), and don’t have the capacity to properly manage the flood of American junk plastic. As a result, tens of millions of tons of improperly managed plastic waste enter the ocean every year (Jambeck, et al.).

Today, there are more than 5 trillion pieces of plastic in the oceans – an amount that gets larger every year (Eriksen, et al.)

Ocean plastic pollution threatens marine wildlife and human food supply systems.

Once plastics are in the ocean, they are exposed to natural elements like wind, waves, and ultraviolet light. Over time, these forces break down plastics into smaller and smaller pieces, including microplastics which are 5mm in size or smaller. Microplastics pose a threat to many species of marine wildlife, including many species of fish, crustaceans, and mollusks that humans around the world depend upon for food (GESAMP, Barboza, et al.).

Plastic pollution is everywhere, not just in the oceans.

But microplastic pollution isn’t just a danger to people who live in coastal areas or who depend on seafood for sustenance. Microplastic pollution has migrated inland, too. Today, microplastics are everywhere – in remote mountain areas, the Great Lakes, the tap water you drink, the air you breathe, and even packaged food and beverages (Kosuth, et al.; Cox, et al.).

The dangers of ingesting microplastics haven’t been completely uncovered by researchers, but the outlook isn’t good. Microplastics are known to carry toxic chemicals, metals, and dangerous biological pathogens (Barboza, et al.).

You release microplastics into the environment every day.

You release microplastic pollution when you do the laundry or drive your car (De Falco; Napper; Ryberg, et al.). If you own clothing made from polyester, you release hundreds of thousands of microplastic particles every time you do the laundry. These particles are too small to be captured by water treatment facilities and are eventually dumped into local waterways (DeFalco, Napper). If you drive a car, road friction causes your tires to eject tiny particles of rubber everywhere you go (Ryberg, et al.).

Plastics cause other forms of pollution, too.

Microplastics and other forms of physical plastic pollution pose a serious threat to ecosystems, the planet, and people, but plastics are hazardous in other ways, too. For starters, most plastics are derived from fossil fuels, through a process that releases significant amounts of greenhouse gases and other pollutants into the atmosphere.

In the U.S., more than 90 percent of plastic waste is incinerated or landfilled, not recycled (EPA, Di). Landfills and incinerators are also significant sources of methane, a highly-potent greenhouse gas, and other airborne and liquid toxins (Andrady). As companies continue to produce more and more plastics, the world will continue dealing with these forms of pollution.

Plastic pollution poses a serious threat to ecosystems, people, and the planet.

Recycling distracts people from confronting companies that make plastic stuff.

Unfortunately, solving the plastic pollution problem isn’t as straightforward as banning all plastics or initiating large-scale cleanup efforts. Plastics have become intertwined with many aspects of modern life, so people depend on them in a variety of ways. Plastics are lightweight, which saves fuel when goods are transported from place to place. Medical products and food packaging made from products can save lives and keep people healthy. There are some plastics the world simply cannot live without (George).

However, companies continue producing new plastics at ever-increasing rates with little to no concern for how they will be managed after use. Of the 9 billion tons of plastics produced since the 1950s, half were made since 2004. On average, companies produce 8.3 percent more new, petroleum-derived non-biodegradable plastic every year (Geyer, et al.).

At the rate companies keep pumping plastic into the world, efforts to clean up plastic pollution seem futile. Recycling was supposed to be the answer to these problems, but it has come up short. America recycles less than 10 percent of its plastic waste, and landfills or incinerates more than 90 percent. Two-thirds of new plastics are used to make products that can’t go into your recycling bin (Heller, et al.).

In the situations listed above, recycling is a distraction, not a solution.

Chapter 3: Recycling helps manufacturers avoid environmental responsibility.

Chapter 5: A path forward.