The Recycling Distraction

The case for moving beyond recycling to reduce waste and prevent pollution.

An MFA thesis project by Rhys Gruebel, Department of Design at The Ohio State University

Since the 1980s, recycling has been a popular American approach to managing consumer waste. Recycling advocates claim that environmental benefits, such as waste reduction, litter prevention, and energy savings, are worth the significant costs of operating municipal recycling systems.

However, evidence from historians, sociologists, scientists, and other researchers demonstrates that the American recycling system was developed to benefit the business interests of manufacturers – not to benefit consumers, or cities, or workers, or the environment.

Recycling distracts people from pursing political solutions to environmental problems, and from demanding systemic changes to reduce waste and prevent pollution. Recycling keeps people busy.

“Busy-ness is a fulfilling sense of work and achievement that often brings positive side effects but fails to reach the central effect. If progress is a flowing stream, busy-ness is an eddy, moving vigorously but not forward.”

Chapter 1

Recycling in America.

What kind of recycler are you?

Are you the casual recycler, who only recycles when it’s convenient, knowing that you could probably do more? Or are you a dedicated recycler, who aspires to recycle as much as possible, so at the end of the week, your recycling bin is more full than your trash can? Maybe you’re the third kind – the evangelist – the true believer whose mission in life is to convince others to be better recyclers.

Regardless of which type of recycler you are, if you live in America, you’ve probably learned about the benefits of recycling. You’ve probably internalized the idea that recycling is the best way for you to do your part to protect the planet from litter and excess waste.

Recycling is more popular than the internet.

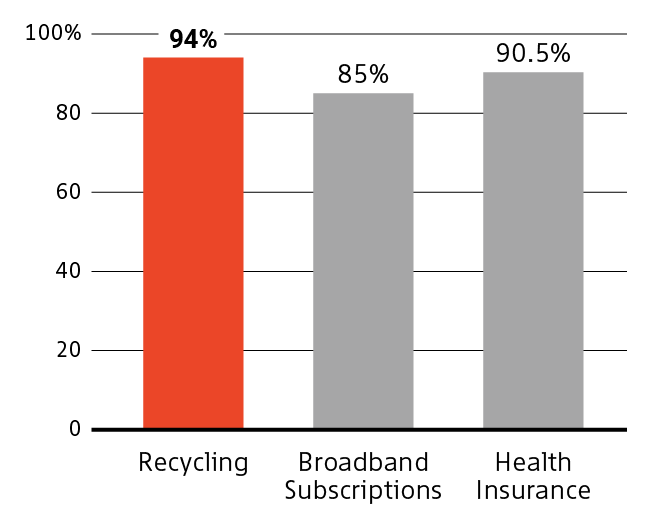

Okay, not exactly. But according to 2020 report by the Recycling Partnership, a leading recycling advocacy group, 94 percent of Americans have regular access to recycling services (Mouw). That’s more than those with broadband internet subscriptions, at 85 percent (US Census Bureau), or who have health insurance, at 90.3 percent (Department of Health and Human Services).

So if recycling is so popular, it must provide significant benefits for the common good, right?

Percentage of Americans with access to recycling, broadband internet subscriptions and health insurance

Sources: The Recycling Partnership, the 2020 US Census, and the Department of Health and Human Services.

The alleged benefits of recycling.

Recycling advocates often promote the following benefits to justify the cost and effort it takes to make recycling work (paraphrased from the EPA’s “Recycling Basics”).

- Recycling reduces waste and conserves natural resources

- Recycling saves energy and prevents pollution

- Recycling provides jobs and other economic gains

An overview of the American recycling system.

A variety of recycling systems are used to capture discarded materials from economic activities in America. Recycling exists in multiple forms across sectors, and often occurs out of sight of American consumers. This project focuses on the most visible type: municipal recycling.

In America, municipal recycling is generally considered to be a public service that is funded by taxpayers, user fees, or a combination of the two (Mouw). American municipal recycling systems are generally aimed at collecting discarded materials from consumer products and packaging.

Depending on where you live, municipal recycling is provided as a curbside service, where trucks come to your house to collect materials, or as a voluntary drop-off format where consumers take recyclables to receptacle at designated locations.

When you put recyclables in the bin, they are collected and transported to a materials recovery facility (MRF)–known as a “merf” in the waste-management business–to be sorted by material type. After sorting, MRFs offer bales of materials for sale to reprocessing companies to be cleaned and processed back into raw materials.

USA: not number one at recycling.

On the global stage America excels at a lot of things, but not recycling. The average recycling rate in America hovers around 30 percent (EPA). This rate includes data on “consumer waste” – common household trash like containers and packaging, and other items like yard trimmings, furniture, and appliances. It does not include construction and demolition debris, sludges from wastewater treatment facilities, or industrial waste (EPA).

Compared to countries like Germany and South Korea, with recycling rates of 68 and 59 percent, respectively, the U.S. doesn’t recycle very well (OCED). On a global scale, the U.S. doesn’t even make the top-ten list of best recycling countries.

Unlike many European or Asian countries with robust recycling cultures, the American recycling system is not a cohesive, singular program operating under a unified set of standards. Instead, a patchwork of thousands of thousands of recycling programs work independently to collect recyclables and manage the materials. Because of this decentralized configuration, recycling guidelines in America vary depending on where you live.

Materials commonly accepted for municipal recycling in America.

Although specific recycling guidelines vary based on where you live, American recycling programs typically collect four broad types of materials from containers and packaging products: glass bottles and jars, aluminum and steel cans, paper and cardboard, and plastic bottles (ASTRX, Mouw).

The system is limited to accepting only a small proportion of the nation’s total waste output.

Although recycling is very popular in America, the current system is rather limited in its ability to reduce waste. Even if the average recycling rate were a perfect 100 percent, at best, municipal recycling would handle only one-third of America’s trash.

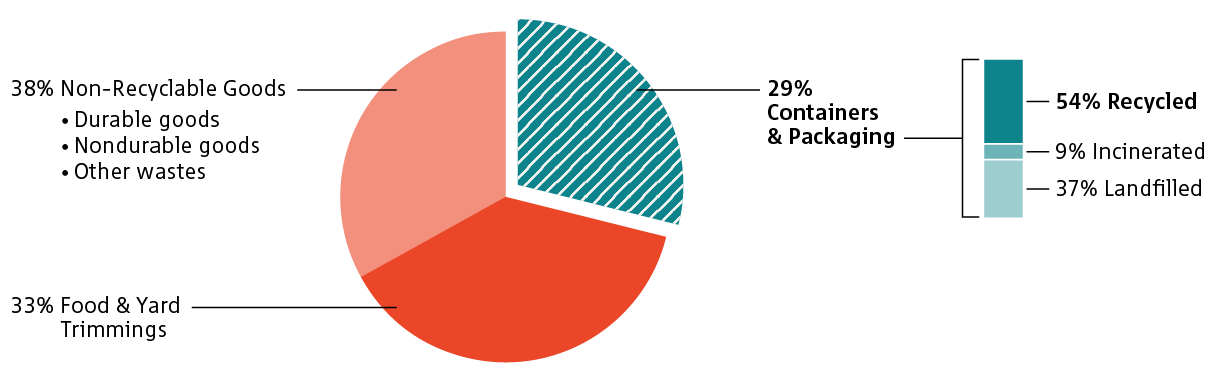

To understand why, let’s take a look at how the EPA divides municipal waste into three broad categories based on the types of goods that are thrown away (EPA).

First is the durable goods category, which applies to products that usually last three years or longer, such as major appliances and furniture. Nondurable goods like clothing, footwear, and household linens typically have a lifespan of three years or fewer. The third category is containers and packaging. Products in this category are usually thrown away within a year of being purchased.

The American recycling system was designed to collect waste from the containers and packaging category only, which in 2018, was 28 percent of the country’s annual municipal solid waste (EPA). Waste from the other two categories, durable and nondurable goods made up the remaining two-thirds of America’s trash.

Major categories of goods in America’s trash (municipal solid waste) in 2018.

Recycling is a distraction.

Despite its widespread popularity, the U.S. recycling system wasn’t designed to solve America’s waste and pollution problems. In fact, the system wasn’t really “designed” at all – it emerged around the 1970s after decades of legal battles between state legislatures and manufacturers over whether to regulate disposable beverage container waste (Elmore, Jaeger, MacBride). Manufacturers sold recycling as a sensible and environmentally beneficial alternative to regulations, and America bought into the idea (Elmore, Jaeger).

Since the 1970s, recycling has enabled manufacturers to shift the costs of managing trash onto the American people and municipal governments. As long as Americans believe recycling delivers meaningful environmental benefits, companies are free to produce billions of disposable, waste-generating products every year, without much scrutiny.

In the following chapters, The Recycling Distraction will show how recycling distracts Americans from three key issues related to waste, pollution, and environmental responsibility:

- Chapter 2: The environmental benefits of recycling are misunderstood and overrated.

- Chapter 3: Recycling helps manufacturers avoid environmental responsibility.

- Chapter 4: Recycling alone won’t stop America from drowning in plastic waste.

Afterward, the project will propose a path forward for addressing these concerns in the future.

Chapter 2

The environmental benefits of recycling are misunderstood and overrated.

To achieve the environmental benefits, manufacturers need to replace virgin materials with recycled materials.

Recycling has the potential to deliver the environmental benefits listed above, but unless products are made with recycled materials, the benefits are either overrated or misunderstood.

The next time you buy something, look at the label. Does it say the package or container is made with 100 percent post-consumer recycled materials? No? Then virgin raw materials and lots of energy were needed to manufacture it. Making products from virgin materials takes a huge toll on the environment and the people who live where natural resources are mined or otherwise extracted – concerns recycling was supposed to help society avoid.

Another downside to using virgin raw materials is that it introduces more overall materials into the economy that will eventually need to be disposed. Unfortunately, in most cases, recycling only delays inevitable disposal (Zink and Geyer).

The only way for recycling to deliver its purported environmental benefits is to displace virgin raw materials with recycled materials during the manufacturing process (Zink and Geyer).

America continues to generate more trash decade after decade.

Recycling was supposed to be a way for Americans to reduce waste. The idea being that if consumers recycle containers and packaging after use, valuable materials won’t end up in a landfill, or worse, become litter.

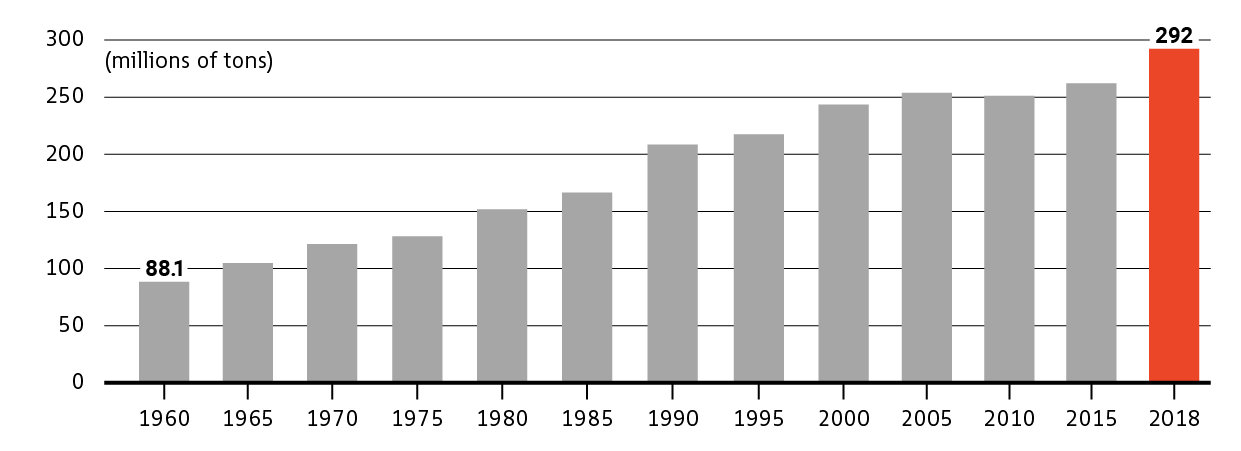

Check out the EPA’s data on municipal solid waste – the official term for “trash” – in the U.S., and you’ll see that America keeps throwing away more stuff year after year.

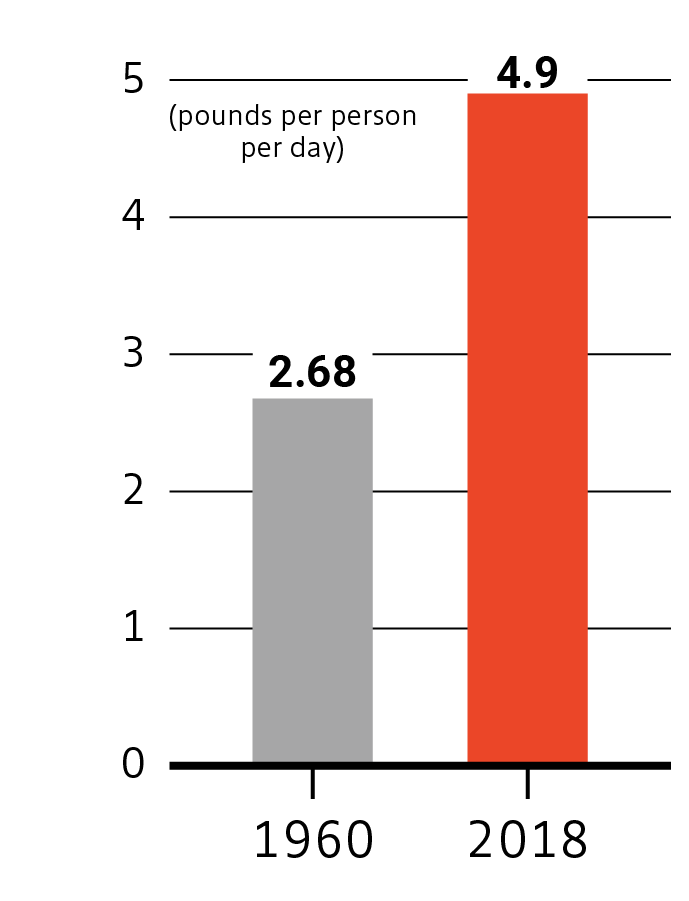

In 1960, Americans generated more than 88 million tons of municipal solid waste at a rate of 2.68 pounds per person, per day. Six decades later, America produced three times as much total waste. In 2018, the most recent year the EPA published data on the subject, Americans threw away more than 292 million tons of trash, at 4.9 pounds per person, per day (EPA).

The dramatic increase in the rate people throw away trash, from 2.9 pounds per person per day in 1960 to 4.9 pounds per person per day in 2018 is a major red flag that recycling isn’t reducing the total amount of stuff America throws away. The American recycling system simply wasn’t designed to keep pace with an economy built to continually generate more and more waste.

Total US municipal solid waste generation, 1960-2018.

Adapted from US EPA National Overview: Facts and Figures on Materials, Wastes and Recycling.

Per-capita trash generation.

Infinite, closed-loop recycling rarely occurs.

The recycling symbol is one of the most recognizable marks in the world. It’s emblazoned on all sorts of consumer products and packaging, including bottles, cans, jars, boxes, bags, and much more. You have probably already encountered the symbol multiple times today.

The symbol is ubiquitous and a powerful daily reminder to participate in recycling. Its triangular, chasing-arrows design suggests that recycling keeps materials in use forever, like some form of industrial reincarnation (Dunaway).

There is potential for some materials to be infinitely recycled. But in reality, recycling is often a slow, downward spiral to the landfill, incinerator, or worse, pollution. Materials often loose value during the recycling process – a phenomenon called downcycling – and will be made into products that won’t be eligible for recycling again (McDonough and Braungart).

In America, plastics are usually downcycled. PET, the plastic used to make soda bottles, and HDPE used to make milk jugs, are the two most-recycled plastics in the U.S. (Heller, Di). More than 70 percent of PET will be downcycled into polyester fiber to make clothing and other textiles (Li Shen and Patel). HDPE is usually downcycled to make storage crates and other durable containers (Andrady). In the U.S., clothing, textiles, and durable products are rarely accepted in curbside recycling systems (ASTRX, Mouw). And forget about plastics #3–7 being beneficially recycled – these “junk plastics” are almost always landfilled, incinerated, or exported to countries in Asia (Di, Brooks, Heller).

Metals, paper, and glass have a better chance of being recycled multiple times, but not by much. Paper is good for 5-7 recycles before its fibers are too small and weak to be recycled again. Metals loose value when alloys are mixed, and unless glass is sorted by color, it will usually be downcycled into products like fiberglass or artificial sand (McDonough and Braungart, MacBride).

More than 70 percent of recycled PET bottles will be turned into polyester fiber, not more bottles.

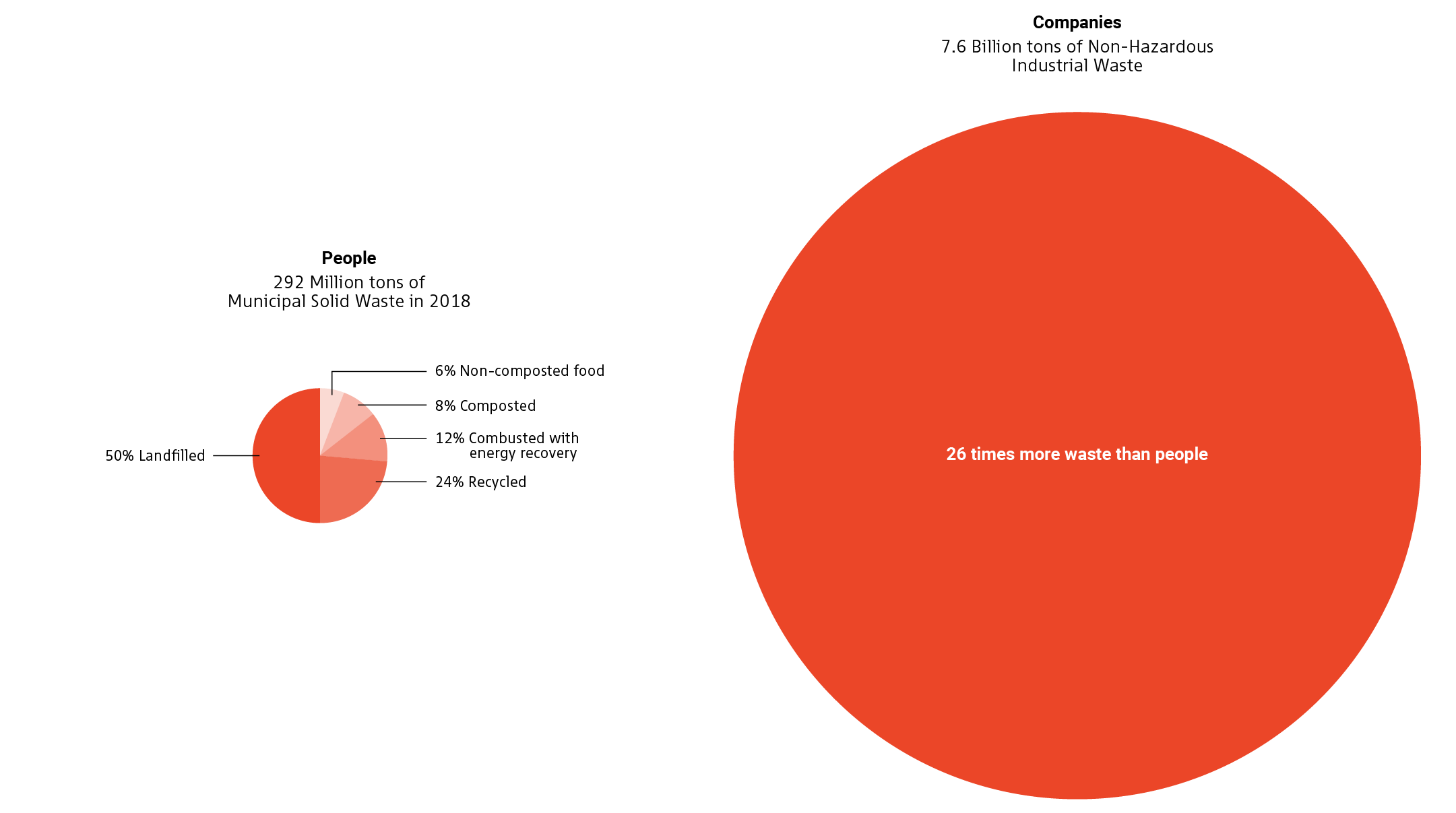

Companies generate far more waste than people.

Another problem with recycling is that it gets more attention than it deserves. Recycling keeps people, organizations, and governments focused on managing and reducing municipal solid waste – trash that is visible to the public. However, the 292 million tons of trash America creates every year is a drop in the bucket compared to the vast amounts of unseen manufacturing waste that companies generate upstream in the economy.

In 2016, the EPA published the Guide for Industrial Waste Management, a 478-page document designed to help factory managers, regulators, and the general public learn best practices for properly disposing non-hazardous industrial waste (EPA). The guide states that manufacturers generate 7.6 billion tons of industrial waste[1] every year. Meaning that during the manufacturing process, companies generate about 26 times more waste than consumers!

Annual waste generated in the United States–people vs. companies.

Sources: US EPA National Overview: Facts and Figures on Materials, Wastes and Recycling; Recycling Reconsidered by Samantha MacBride; US EPA Guide for Industrial Waste Management.

Without comprehensive data, companies are shielded from public scrutiny about industrial waste.

The EPA started collecting data about municipal solid waste in 1960, so we know a lot about the stuff people throw away and how trash is managed. Today, most states conduct comprehensive studies to learn what’s in their trash and where the materials go after being collected. The EPA compiles and shares this data with the public so people and governments can make informed decisions about municipal-waste-management issues (EPA).

Unfortunately, when it comes to issues related to industrial waste, people and lawmakers are relatively uninformed. For decades, companies and industry groups have fought to make sure reporting data about industrial waste remains voluntary (MacBride). As a result, the American public knows very little about the characteristics of industrial waste and how companies dispose of it (MacBride).

Without robust and accurate data about industrial waste, it’s very difficult for people and lawmakers to hold manufacturers accountable for their fair share of environmental problems.

Recycling’s benefits are mostly economic.

Recycling hasn’t done much to reduce waste in America, but it does provide some economic benefits. The EPA’s 2020 Recycling Economic Information (REI) report shows that every year, the recycling economy supports about 681,000 jobs, $37.8 billion in wages, and $5.5 billion in tax revenues (EPA).

One important caveat of the REI, is that the report includes economic data from industries indirectly related to recycling, such as the power plants that supply energy to run recycling facilities, and information about materials collected for recycling outside municipal systems, such as construction waste and rubber from used tires.

Recycling has many negative impacts on workers and neighborhoods.

Recycling’s economic benefits come at a huge cost to workers and people who live near recycling facilities.

The work of collecting, transporting, and sorting recyclables is incredibly hazardous. In 2020, the Bureau of Labor Statistics found that trash and recycling collection is the fifth most dangerous civilian job in the country (BLS). And work at the sorting facilities isn’t much better. High-tech equipment enables much of the sorting process to be automated, but a surprising amount of human labor is still needed to remove contaminants from the waste stream. Sorters work all day next to heavy, fast-moving equipment, and are exposed to hazardous chemicals, persistent dust, and harmful objects on the sorting line (NIOSH).

Unfortunately, in urban America, MRFs and other waste-processing facilities are typically located in industrial zones next to low-income neighborhoods (MacBride). Residents in these areas are disproportionately impacted by negative side effects from MRFs, like excess noise, pollution, and the continual flow of trash trucks driving through the neighborhood.

Recycling distracts people from confronting an economy designed to create waste.

Take

Extract finite natural resources

Make

Manufacture single-use disposable goods

Waste

Dispose containers and packaging

Take

Extract finite natural resources

Make

Manufacture single-use disposable goods

Waste

Dispose containers and packaging

The American consumer-goods economy is a linear, take-make-waste system. Companies extract raw materials from the earth to make goods for consumers to buy. The goods are designed to be disposable so companies can sell goods faster. Waste and pollution are simply inevitable results of a linear economy that defines progress as producing more goods year after year.

Problems created by this economy, such as excess waste and litter, are often framed in terms of the individual consumer. Trash is called “consumer waste” and the word “litter” is used to highlight pollution generated by individual people. And “consumerism” carries a negative connotation, suggesting that consumers’ obsessive purchasing habits are solely to blame for widespread environmental problems. But focusing conversations about environmental problems in consumer-centric terms leaves the role of producers (manufacturers) out of the conversation, and therefore out of reach of criticism.

Where is the widespread criticism of “productionism”?

Since the 1960s, recycling has been promoted as the antidote to the excesses of the linear economy. People learn through educational programming and government-sponsored PSA campaigns, that it is their duty to reduce waste and prevent pollution by recycling (Jaeger, Dunaway). Recycling is promoted as the way people can “close the loop” to keep valuable materials in use for perpetuity, offering consumers a sense of redemption for buying disposable products (Dunaway).

Unfortunately, recycling distracts consumers from confronting the system that creates the conditions for so much waste to be created in the first place. In the next chapter, we’ll see how the beverage industry, not environmental groups or a government initiative, helped make recycling popular in America.

Chapter 3

Recycling helps manufacturers avoid environmental responsibility.

Before recycling was popular, a refillable-container system prevented trash.

Today, consumers are accustomed to throwing away containers and packaging after use. Before the 1950s, products like beer, soft drinks, milk, and yogurt came in refillable “two-way” glass containers (Jaeger, Elmore). Two-way containers were durable, cleanable, and easily refilled with new product multiple times.

During this era, consumers paid a refundable cash deposit, sometimes as much as 40 percent of the purchase price, when they bought products in returnable containers (Elmore). After use, consumers returned the empty containers to the manufacturer, and received their deposit back. Containers like glass soft drink bottles typically made 25-50 round trips between bottlers and consumers (Elmore).

The two-way container system used in the first-half of the 20th century eliminated waste because manufacturers put a price on trash. Empty containers were valuable to consumers and companies alike. Consumers were incentivized to return used bottles instead of throwing them away, and manufacturers saved money on the costs associated with purchasing new containers.

In the 1950s, beverage companies dismantled the two-way container system to boost profits.

After World War II, the beverage industry changed the way people consumed its products. In the early 1950s, many beer and soft drink companies stopped bottling beverages in refillable containers in favor of disposable one-way containers (Elmore, Jaeger). Using disposable containers helped companies avoid the transportation and cleaning costs for refillable bottles on the return trip. (Elmore). Beverage companies dismantled the highly successful two-way container system in order to streamline their operations and make more money (Elmore).

And with disposability, came litter.

Unsurprisingly, switching from the two-way container system to a one-way system with disposable containers came with some environmental drawbacks (Jaeger, Elmore). As more and more disposable cans and bottles were sold, cities and towns were naturally forced to collect, transport, and dispose more container waste.

When companies switched to disposable containers, they also eliminated the need for consumers to pony up cash deposits when they bought products in returnable containers. Deposits ensured empty containers had economic value, but without them, used bottles were practically worthless (Elmore).

In addition to needing to deal with more waste after the switch to disposable containers, America was also forced to confront a new form of pollution tainting the landscape in the early ‘50s: litter (Elmore, Jaeger). Litter quickly became a significant concern for environmentally minded Americans, many of whom blamed manufacturers for creating the problem.

In the mid-1950s, the fight over litter entered political arenas.

The public’s concern over the litter problem became political in 1953 when lawmakers in Maryland and Vermont attempted to restrict the use of single-use disposable beverage containers (Elmore). Maryland legislators proposed a bill requiring refundable deposits on all disposable beer bottles, but it did not have enough support to become law (Elmore). Vermont was marginally more successful. In February 1953, Vermont passed a law banning single-use disposable beer bottles in the state, which one estimate showed reduced litter by up to 90% (Jaeger). Unfortunately, Vermont’s law was struck down after only four years. In 1957, Vermont’s newly created Litter Commission repealed the law after meeting with consultants from the beverage and packaging industries. These consultants urged the Litter Commission to dismantle the law, saying it could set a dangerous precedent for manufacturers in the future (Jaeger).

Between and the late 1970s, lawmakers across the country proposed thousands of laws aimed at restricting the use of non-returnable beverage containers. Very few became law (Elmore). Today, only ten states have container deposit laws (NCSL).

The beverage and packaging industries developed a strategy to blame people for litter.

Around the time Maryland and Vermont were working on laws to restrict the use of single-use disposable products, the beverage and packaging industries developed a joint strategy to protect themselves from the threat of future legislation (Elmore). Companies like Coca-Cola and Pepsi knew that if Americans continued blaming manufacturers for the litter problem, it was likely that more states would pursue laws restricting disposable containers and packaging (Elmore). Container deposit laws posed a serious threat to the industry’s profitability and their public image (Elmore, Jaeger).

Their strategy was simple: avoid regulations on disposable packaging by blaming individual consumers, not manufacturers, as the source of the widespread litter problem (Jaeger, Elmore). This strategy is known as individualism, or the individualization of environmental responsibility (Maniates).

To enact their strategy, companies needed to change the way Americans talked about waste, pollution, and environmental responsibility. So in 1953, companies from the beverage, packaging, and canning industries set aside their competitive differences to establish a third-party organization to carry their message to lawmakers and the general public: Keep America Beautiful (KAB).

The beverage and packaging industries established Keep America Beautiful to distract Americans with busywork.

Keep America beautiful was established as an anti-litter organization. From the outside, KAB seemed to be a grassroots operation working to address litter-related problems for the public good. But in reality, KAB’s mission was to advance the corporate strategy of individualization – blaming people for systemic problems like litter – through advertising, education campaigns, and lobbying activities (Jaeger, Elmore, Dunaway).

“KAB’s central objective was to deflect accusations that corporations were to blame for the country’s growing litter problem… Through targeted education programs, national publicity campaigns, and local clean-up drives, KAB worked to persuade consumers that private citizens, not corporate citizens, should be responsible for waste disposal.” (Elmore, p. 243)

Today, KAB has more than 700 affiliates across the country (KAB). The organization has embedded itself within all levels of civil society to keep Americans busy cleaning up litter, planting trees, and recycling (Jaeger, KAB). These activities may provide modest environmental benefits, but they don’t address litter problems at the source: companies that manufacture billions of non-biodegradable disposable products every year.

KAB keeps Americans distracted with busywork so they don’t challenge manufacturers on environmental issues through political channels.

KAB sold individualism to Americans through national advertising campaigns.

A full-page “Susan Spotless” ad by Keep America Beautiful, from Time Magazine, April 2, 1965.

During the mid-1960s, Keep America Beautiful ran emotionally charged ads with the character Susan Spotless. In the ads, Susan, a supposed emblem of purity, shamed her parents with a pointed finger as a reminder to avoid littering.

Keep America Beautiful. Photograph by the author of the item in his personal collection.

The beverage industry used KAB to change the way Americans think and talk about environmental responsibility – from blaming manufacturers for waste and pollution, to blaming individual people. KAB accomplished this goal through advertising and widespread public service announcement (PSA) campaigns (Dunaway).

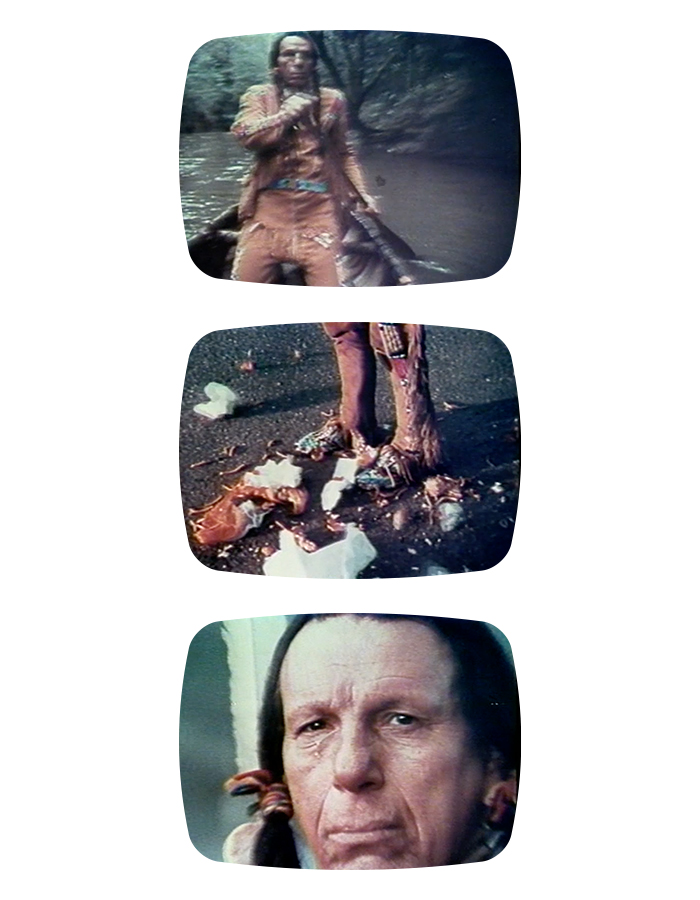

In the 1950s and ‘60s, KAB created ad campaigns such as “Susan Spotless” and “Pigs”, to stoke a sense of moral duty in Americans to eschew littering. However, KAB’s most famous – or rather infamous – effort was the now iconic “Crying Indian” campaign that debuted in 1971, exactly one year after the first Earth Day (Dunaway, Jaeger, Elmore).

The Crying Indian ad campaign featured a television commercial starring actor Iron Eyes Cody dressed in a historic, Native-American-looking outfit, complete with long, braided hair and a feather over one ear. In the commercial, Cody paddles a canoe down a bucolic stream into a modern-day setting, only to have a bag of fast-food trash thrown at him by passing motorists. The motorist’s careless act forces a single tear from the stoic character, communicating deep feelings of sadness and regret about the state of the world. A narrator drives the point home by closing the ad with the guilt-ridden tagline, “People start pollution. People can stop it.”

Keep America Beautiful used the Crying Indian ad campaign to stoke a national sense of guilt about litter, waste, and pollution (Dunaway). The campaign set the stage for recycling to enter the mainstream by convincing people that only individual actions, not regulations or systemic change, can protect the environment from the excesses of economic activity (Jaeger, Elmore).

01 | Still images from the 1971 “Help Fight Pollution” (Crying Indian) television commercial

The iconic “Crying Indian” commercial starred Italian-American actor “Iron Eyes” Cody and ended with the closing line “People start pollution. People can stop it.”.

The commercial launched a massive ad campaign that convinced Americans that individual people – not companies – created pollution, and therefore, people were responsible for cleaning it up.

Keep America Beautiful and the Ad Council. Stills captured from a digital video file courtesy of the Ad Council Archives, University of Illinois.

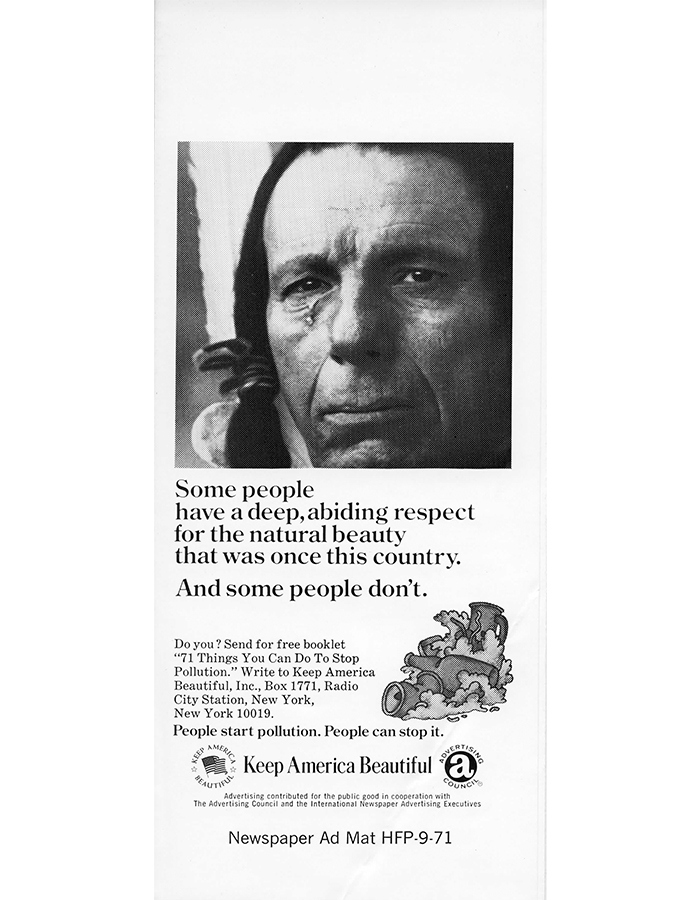

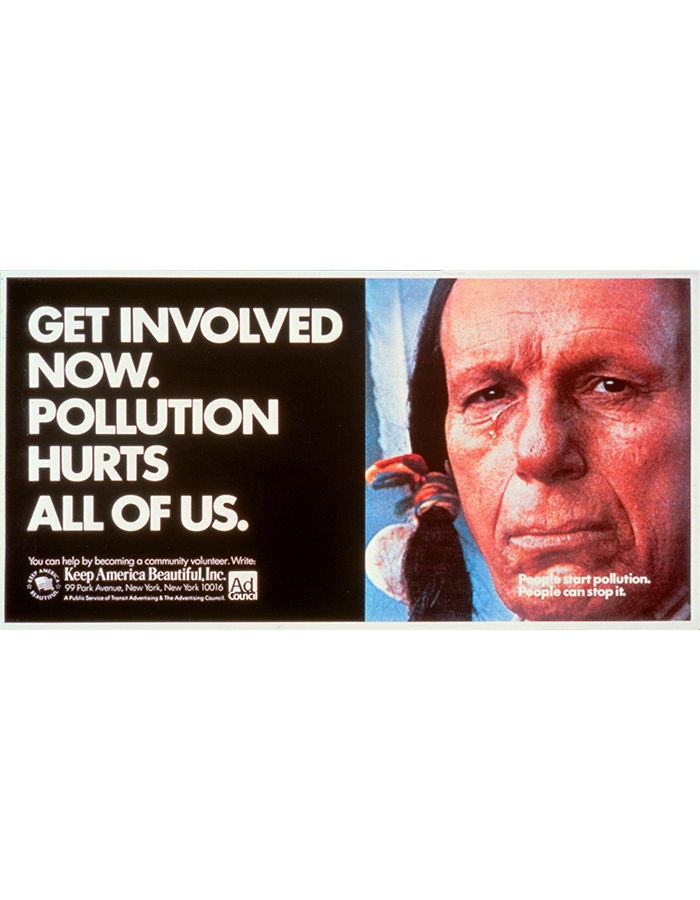

02 | “Help Fight Pollution” print advertisement, 1971

During the 1970s, the television commercial was adapted for distribution across multiple forms of media. Here, a print ad encouraged people to request Keep America Beautiful’s booklet, “71 Things You Can Do To Stop Pollution.”, for ideas on activities to benefit the environment.

Keep America Beautiful and the Ad Council. Courtesy of the Ad Council Archives, University of Illinois.

03 | “Help Fight Pollution” bilboard advertisement, 1971

The iconic photo of the teardrop on Cody’s face is used throughout the campaign. Here, in this bilboard advertisement, the image is cropped tightly to emphasize the tear and the sorrowful expression on Cody’s face. These emotional elements were designed to underscore the written message and motivate viewers into action.

Keep America Beautiful and the Ad Council. Courtesy of the Ad Council Archives, University of Illinois.

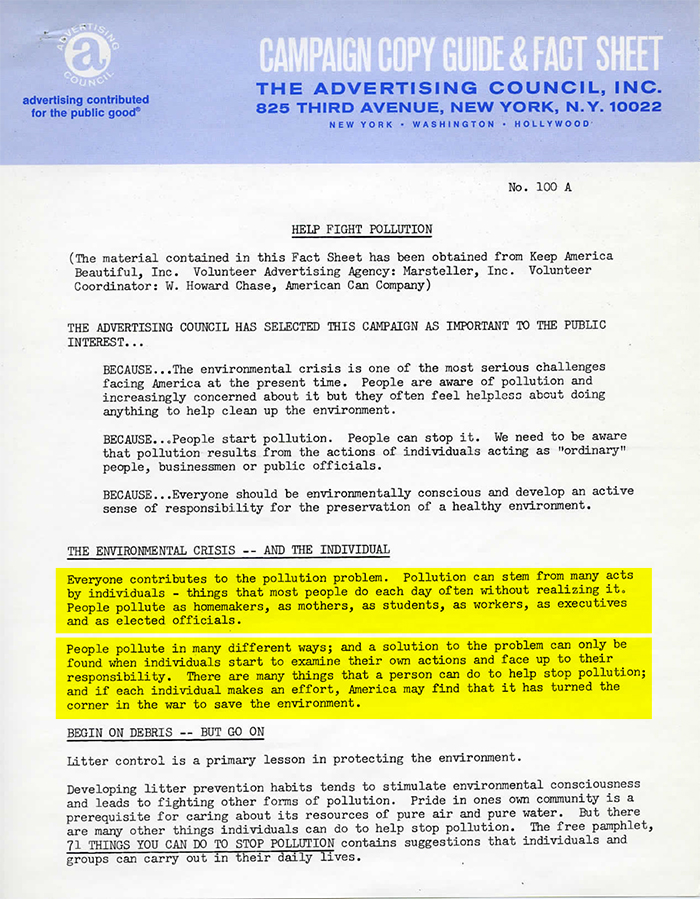

04 | “Help Fight Pollution” copy guide and fact sheet (page 1), 1972

In 1972, the Ad Council sent this “Campaign Copy Guide & Fact Sheet” to radio broadcasters along with audio recordings and scripts for 10-, 30-, and 60-second public service announcements.

The guide informed broadcasters about individualized environmentalism and how to communicate campaign messages to audiences. It is evidence of Keep America Beautiful’s strategic efforts to blame people for pollution while ignoring the role of Industry in creating environmental problems.

Note that an executive from the American Can Company is listed as a “Volunteer Coordinator” for the campaign.

Keep America Beautiful and the Ad Council. Courtesy of the Ad Council Archives, University of Illinois. Highlighting added by the author for emphasis.

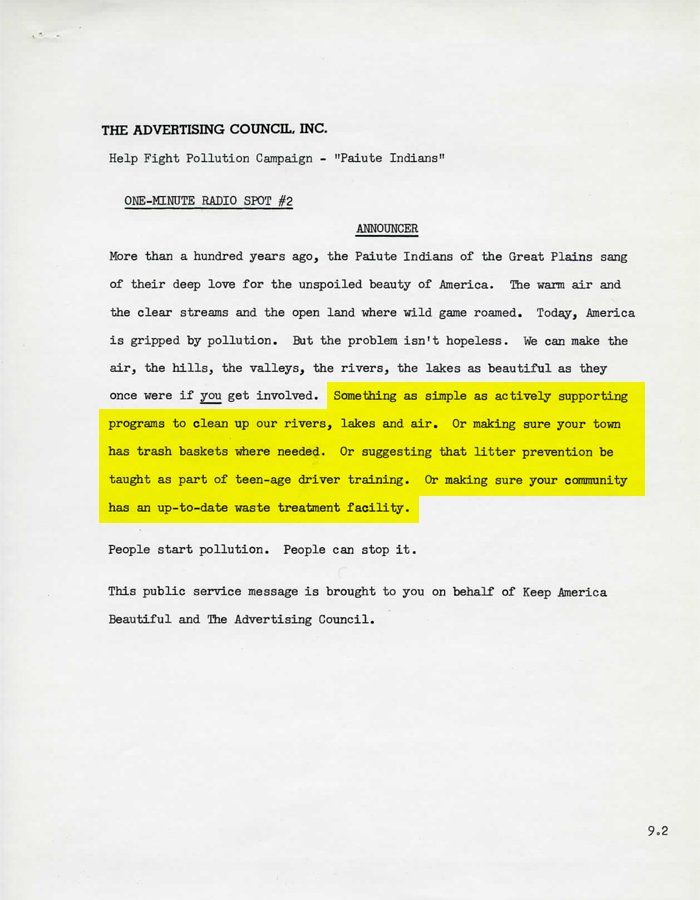

05 | “Help Fight Pollution” campaign radio script, 1972

The Ad Council provided this script for a 60-second public service announcement to radio broadcasters in 1972. The radio ads echoed the sentiments from the television commercial, relying on guilt as a motivational lever. The first paragraph concludes with suggestions for how people could prevent litter and clean up pollution – none of which involve scrutinizing companies for their roles as polluters.

Keep America Beautiful and the Ad Council. Courtesy of the Ad Council Archives, University of Illinois. Highlighting added by the author for emphasis.

Individualism paved the way for ubiquitous recycling.

In the mid- to late-1970s, KAB followed up their advertising efforts with educational campaigns designed to spread the word about volunteer litter cleanups to thousands of schools, non-proft organizations, and local governments (Jaeger). KAB also developed and promoted their “Clean Community System (CCS),” a program to help local government organizations track and monitor progress on cleaning up litter in their communities (Jaeger).

Despite these efforts, cities across the country struggled to keep up with the increasing amounts of trash being thrown away each year (Jaeger). In the early 1980s, the country experienced a solid waste crisis. Americans feared there wasn’t enough space in the nation’s landfills to hold all the stuff they were throwing away (Jaeger).

In 1982, KAB ramped up their efforts to promote recycling. The organization worked in tandem with the beverage and packaging industries to convince lawmakers, environmental organizations, and the general public to adopt recycling instead of container deposit laws to prevent litter. Recycling was positioned as a “win-win-win” solution to problems with container waste (Jaeger, Elmore).

Recycling boomed in the United States during the 1980s and ‘90s. In 1989, there were roughly 600 curbside recycling programs across the country. Three short years later in 1992, there were more than 4,000 (Elmore).

Individualism is a distraction.

Today, in America, recycling is institutionalized individualism. Recycling and other activities that happen at the individual level, like litter cleanups, are environmental busy work (MacBride). At best, they have marginal reductions on waste and pollution in the short term, but long term, they distract people from scrutinizing the underlying systems that produce so much waste in the first place (Maniates, Maniates).

Since the 1950s, the beverage and packaging industries have made significant efforts, many through Keep America Beautiful, to convince Americans that small activities like recycling, can add up to big change on environmental problems. History shows us that this is part of a a strategy companies use to avoid sensible regulation of disposable products.

Recycling keeps you acting in the realm of the individual – that is to say, it keeps you distracted with individualized activity so you don’t consider using political channels to address environmental problems. When it comes to limiting waste and pollution caused by disposable products, companies would rather you recycle instead of vote.

Chapter 4

Recycling won’t stop America from drowning in plastic waste.

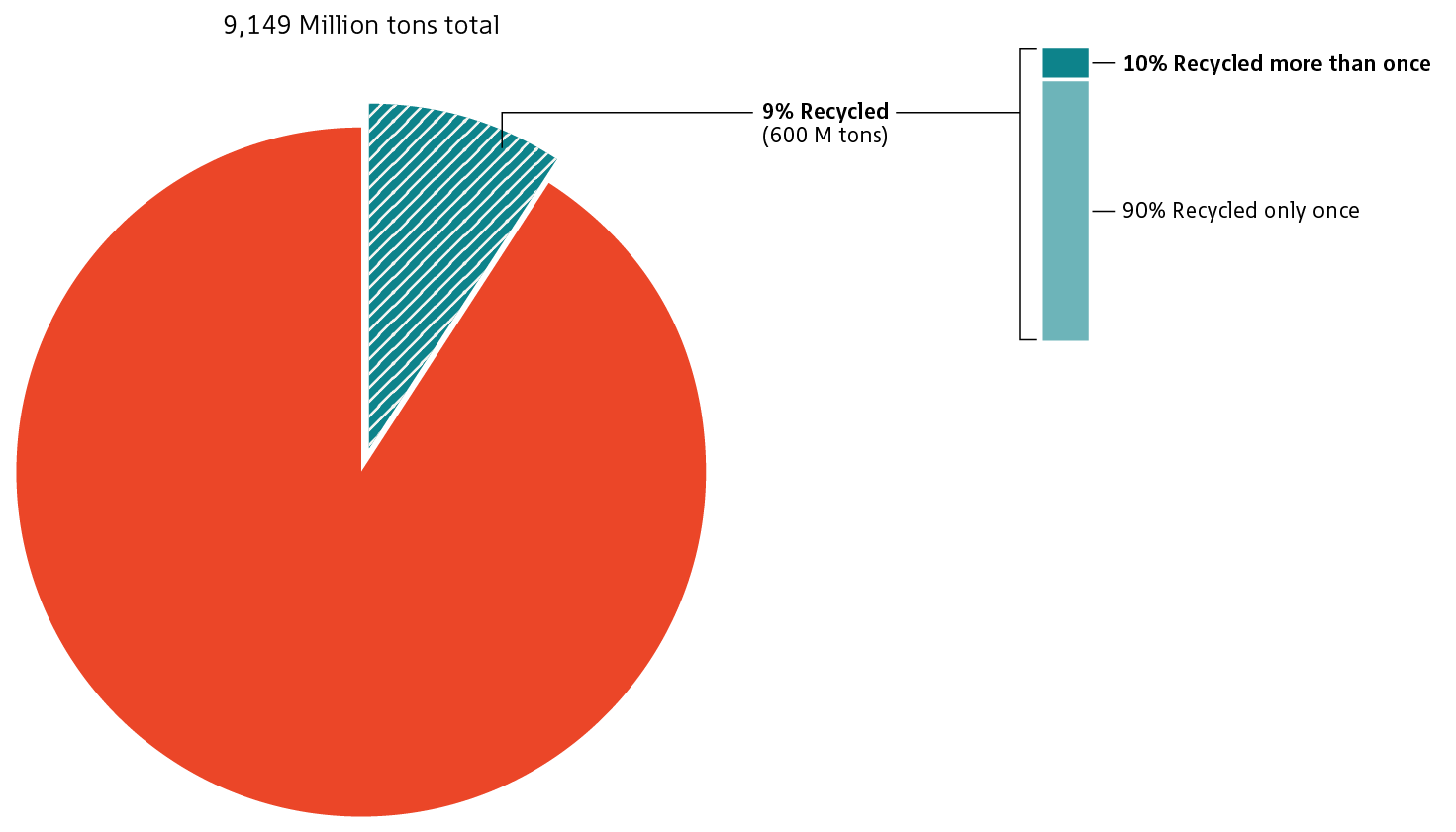

Most plastics have never been recycled.

Aside from steel and concrete used in the construction industry, plastics are one of the most abundant human-made materials on earth (Geyer, et al.). Plastics were first used to manufacture goods in the 1920s, but the material wasn’t as ubiquitous then as it is today. World War II marked a turning point for plastics as global plastics production ramped up significantly in the 1950s. Since then, more than nine billion tons[1] of plastics have been produced around the world (Geyer, et al.).

As of 2015, fewer than 10 percent of all plastics ever made have been recycled, and only a tiny fraction of those have been recycled more than once (Geyer, et al.). Sadly, most plastic waste is landfilled, incinerated, or ends up as pollution (Geyer, et al.).

In the United States, more than three-quarters of plastic waste is buried in landfills, not recycled (Heller, Di).

Global Recycling Rate for All Plastics Ever Made (1950-2015)

Source: Geyer, Jambeck, and Law, “Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made.” Science Advances, 2017.

With more factories being built, the plastics problem will likely get worse.

Since the 1960s, companies have produced more and more disposable plastics. As a result, the proportion of plastics in America’s trash continues to grow. In 1960, less than 1 percent of America’s trash was plastic. Three decades later in 1990, it was 8.2 percent. And in 2018, plastics accounted for 12.2 percent of materials in America’s garbage.

Unfortunately, recycling hasn’t kept pace with the rate America generates plastic trash. Since the 1990s, the average recycling rate for plastics in the U.S. has been 6-9 percent (EPA, Heller, Di).

The American recycling system simply wasn’t designed to process the amount of plastic waste America generates. One reason for this is that 60 percent of America’s plastic waste isn’t even eligible for municipal recycling (Heller, Di). The U.S. recycling system was designed to collect only discarded containers and packaging – bottles, cans, and the like. Other types of waste, for example, from automotive products or construction debris, are not accepted in U.S. curbside recycling programs.

America’s abysmally low recycling rate for plastics is troubling when you consider that since 2010, petrochemical companies have been investing billions to build factories to produce millions of tons of new plastics (ACC, Yale360).

If the current U.S. recycling system is inadequate to capture existing amounts of plastic waste, how could it possibly stop America from drowning in the flood plastics from hundreds of new factories?

The link between the U.S. recycling system and ocean plastic pollution.

For decades, many U.S. recycling programs have collected low-value plastics – #3 Polyvinyl Chloride (PVC), #4 Low-Density Polyethylene (LDPE), #5 Polypropylene (PP), #6 Polystyrene (PS), and the #7 “Other” category – but haven’t actually recycled them. These plastics are used to used to make a wide variety of commonly available products like yogurt cups, coffee cup lids, straws, take-out containers, and toys.

Instead of being recycled, plastics #3-#7 are usually landfilled or incinerated (Brooks, Di, EPA). Sometimes, American waste-management programs become so overwhelmed with plastic waste they ship the materials overseas (Brooks, et al.).

From 1992 to 2016, the U.S. exported 29 million tons of plastic waste to China and Hong Kong (Brooks, et al.). After China tightened restrictions on foreign waste in 2018, the U.S. enlisted other countries to accept its junk plastic, like Thailand and Malaysia (Brooks, et al., Wang, et al.).

Unfortunately, many countries that import American plastic waste often have underdeveloped waste-management systems themselves (by U.S. standards), and don’t have the capacity to properly manage the flood of American junk plastic. As a result, tens of millions of tons of improperly managed plastic waste enter the ocean every year (Jambeck, et al.).

Today, there are more than 5 trillion pieces of plastic in the oceans – an amount that gets larger every year (Eriksen, et al.)

Ocean plastic pollution threatens marine wildlife and human food supply systems.

Once plastics are in the ocean, they are exposed to natural elements like wind, waves, and ultraviolet light. Over time, these forces break down plastics into smaller and smaller pieces, including microplastics which are 5mm in size or smaller. Microplastics pose a threat to many species of marine wildlife, including many species of fish, crustaceans, and mollusks that humans around the world depend upon for food (GESAMP, Barboza, et al.).

Plastic pollution is everywhere, not just in the oceans.

But microplastic pollution isn’t just a danger to people who live in coastal areas or who depend on seafood for sustenance. Microplastic pollution has migrated inland, too. Today, microplastics are everywhere – in remote mountain areas, the Great Lakes, the tap water you drink, the air you breathe, and even packaged food and beverages (Kosuth, et al.; Cox, et al.).

The dangers of ingesting microplastics haven’t been completely uncovered by researchers, but the outlook isn’t good. Microplastics are known to carry toxic chemicals, metals, and dangerous biological pathogens (Barboza, et al.).

You release microplastics into the environment every day.

You release microplastic pollution when you do the laundry or drive your car (De Falco; Napper; Ryberg, et al.). If you own clothing made from polyester, you release hundreds of thousands of microplastic particles every time you do the laundry. These particles are too small to be captured by water treatment facilities and are eventually dumped into local waterways (DeFalco, Napper). If you drive a car, road friction causes your tires to eject tiny particles of rubber everywhere you go (Ryberg, et al.).

Plastics cause other forms of pollution, too.

Microplastics and other forms of physical plastic pollution pose a serious threat to ecosystems, the planet, and people, but plastics are hazardous in other ways, too. For starters, most plastics are derived from fossil fuels, through a process that releases significant amounts of greenhouse gases and other pollutants into the atmosphere.

In the U.S., more than 90 percent of plastic waste is incinerated or landfilled, not recycled (EPA, Di). Landfills and incinerators are also significant sources of methane, a highly-potent greenhouse gas, and other airborne and liquid toxins (Andrady). As companies continue to produce more and more plastics, the world will continue dealing with these forms of pollution.

Plastic pollution poses a serious threat to ecosystems, people, and the planet.

Recycling distracts people from confronting companies that make plastic stuff.

Unfortunately, solving the plastic pollution problem isn’t as straightforward as banning all plastics or initiating large-scale cleanup efforts. Plastics have become intertwined with many aspects of modern life, so people depend on them in a variety of ways. Plastics are lightweight, which saves fuel when goods are transported from place to place. Medical products and food packaging made from products can save lives and keep people healthy. There are some plastics the world simply cannot live without (George).

However, companies continue producing new plastics at ever-increasing rates with little to no concern for how they will be managed after use. Of the 9 billion tons of plastics produced since the 1950s, half were made since 2004. On average, companies produce 8.3 percent more new, petroleum-derived non-biodegradable plastic every year (Geyer, et al.).

At the rate companies keep pumping plastic into the world, efforts to clean up plastic pollution seem futile. Recycling was supposed to be the answer to these problems, but it has come up short. America recycles less than 10 percent of its plastic waste, and landfills or incinerates more than 90 percent. Two-thirds of new plastics are used to make products that can’t go into your recycling bin (Heller, et al.).

In the situations listed above, recycling is a distraction, not a solution.

Chapter 5

A path forward.

America needs a new approach for solving waste and pollution problems.

For decades, popular American approaches to protecting the environment have centered around people acting at the individual level. The popular mantra, “Think globally, act locally,” often guides these efforts and informs the mindset that small actions will add up to big change (Maniates). Individualized activities like recycling, picking up litter, and buying “green” products have not produced significant change toward a cleaner, healthier planet. America throws away more trash every year. Litter is still a widespread problem, despite Keep America Beautiful’s efforts to combat it (KAB). Companies keep the treadmill of production moving forward by extracting natural resources and generating waste and pollution on a scale that far outweighs the actions of individual people.

These issues are too complex, dynamic, and interconnected to solve with traditional approaches to problem solving (Dorst). A new approach is needed for changing the political and economic systems that make waste and pollution possible.

This project proposes the following path forward to make progress on these issues.

First, let’s change the way people talk about waste, pollution, and environmental responsibility.

The tagline from the iconic Crying Indian ad campaign, “People start pollution. People can stop it.”, was instrumental in changing the way Americans talk about environmental responsibility. These two sentences cemented individualism into the collective American psyche and laid the groundwork for the modern recycling movement.

The problem with this tagline is that it completely ignores the role companies have in creating environmental problems. Companies, not people, create the conditions for waste and pollution when they choose to manufacture billions of non-biodegradable disposable products annually.

The next time you fret about recycling, or join a litter cleanup event in your community, consider this:

- Companies determine if products will be disposable or not.

- Companies choose which materials to use during manufacturing.

- Companies design products to be recyclable or not.

- Companies determine how many products will be made.

- Companies decide if waste and pollution are inevitable or not.

Things people can do in the short term.

In the short term, continue recycling. The recycling economy creates jobs and provides revenue for municipalities. To stop recycling now will have negative financial consequences for workers and local governments – people could lose their jobs, and municipalities would have less money to fund other public services (MacBride).

But you stop agonizing about being a perfect recycler. Many products simply aren’t designed to be recycled in the current system. Check your local city or waste-management company’s website to learn which items are accepted for recycling in your area, then abide by the guidelines. And stop wish-cycling. Putting the wrong items into your recycling bin can do more harm than good. Materials like extension cords, wire coat hangers, and plastic grocery bags damage sorting equipment, put workers in danger, and contaminate bales of sorted recyclables.

Things people can do in the medium- to long-term.

You need to make waste, pollution, and environmental issues political again. Expand the idea of “doing your part” to moving beyond your role as a consumer. Recycling, picking up litter, and buying green products all sound like good ideas, but they don’t change the underlying systems that make waste and pollution possible in the first place. Americans should set aside their consumer identities, and reclaim their roles as active, engaged citizens.[1]

Demand that lawmakers enact sensible legislation to make manufacturers put a price on trash. Container deposit laws, product bans, and taxes can be effective tools for reducing waste, preventing pollution, and improving recycling [to add sources]. Then, go vote on these issues. Remember, industries spend millions of dollars every year lobbying elected officials to write laws that prioritize business interests above environmental protection. Companies influence the political process to protect their interests – you should, too.

Things environmental organizations can do.

Environmental organizations should stop working to achieve polite, incremental changes on waste and pollution issues.[2] Instead, adopt a confrontational mindset to challenge producers directly, in political and public arenas. Use your platforms to change the public narrative on waste, pollution, and environmental responsibility away from individualized solutions. If your list of “top ten things you can do for the environment” doesn’t include voting, it’s incomplete. Instead of spending time writing top-ten lists, redirect consumers’ energy toward collective civic action, like pursing policy change to hold producers accountable for their share of waste and pollution problems.

Refilling is better than recycling, and ‘reuse’ is not a craft project.

When beverage companies like Coca-cola and Pepsi sell 1,000,000 disposable PET bottles every minute, will skipping the straw or turning empty bottles into planters make a difference (Reuters)? If companies switched back to refillable containers, there’s no need to worry about recycling empties.

History shows us that excessive waste is not always an inevitable byproduct of producing and consuming goods. Remember how companies sold beer, soft drinks, and other beverages in durable, refillable containers before the 1950s? Let’s do more of that. In 1972, the EPA acknowledged that refilling beverage containers is better for the environment than disposable ones. Today, despite the agency’s affinity for recycling, still lists refilling (reuse) as a preferred waste management approach (EPA).

Today, durable, refillable containers are making a comeback. Companies like Loop are working with major consumer products manufacturers to sell popular household products in refillable containers. And in February 2022, Coca-cola announced a target to sell at least 25% of its beverages in two-way containers by 2030. The efforts by these two companies adopt business models based on two-way containers is encouraging, but more can be done to prevent single-use packaging waste.

The circular economy framework aims to eliminate waste by design.

The best way to prevent waste is to avoid creating it in the first place. The circular economy provides a framework – a structure for guiding a system – for reimagining the entire global economy to be more environmentally and socially responsible (EMF). Proponents of the circular economy aim to help companies design goods in a way that doesn’t rely on extracting natural resources, consuming fossil fuels, and generating waste and pollution.

More importantly, the circular economy doesn’t position recycling as the one-sized-fits-all solution to sustainability problems; it puts recycling into context of other approaches for reducing or preventing waste by design.

Identify individualism to see past the distraction.

Recycling has a role to play in achieving a more sustainable future. However, it’s important to understand the limitations of recycling and when it is an appropriate waste-management strategy.

It’s also beneficial to learn to how to identify individualism, and when it is used to protect the status quo. The next time you read an article about being more environmentally friendly, or see a top ten list of things you can do to protect the earth, keep the following criteria in mind. Spotting individualism can help you think more critically about the root sources of environmental problems and pursuing meaningful solutions.

How to identify activities rooted in individualism:

- Is the activity based on the hope that small actions will add up to big results without using laws, regulations, or other policy mechanisms to guide the process?

- Does the activity require you acting as a consumer instead of a politically engaged citizen?

- Does the activity avoid confrontation with the companies or industries who created the conditions for the problem?

- Does the activity rely on using guilt, patriotism, or another emotional lever to motivate you to participate?

- Does the activity assume that the roles and responsibilities of people are equal or more than those of companies and industries?

If you answered ‘yes’ to any of these questions, you may have successfully identified individualism.